Dating apps: security and privacy

Privacy, data monetization, scams, and cyber protections… focus on dating apps.

Privacy, data monetization, scams, and cyber protections… focus on dating apps.

In 2017, Judith Duportail, a journalist from The Guardian, asked Tinder to send her all the information that the application had collected about her since the creation of her account (which she had held at the time for four years). She received an 800-page report that included “links to the location of [her] Instagram photos, [her] education level, the age of men she was interested in, the number of Facebook friends she had,” as well as “the date and location of each online conversation with each of [her] matches.

Alessandro Acquisti, professor of information technology at Carnegie Mellon University, who participated in Judith Duportail’s survey, writes: “Tinder knows a lot more about you when it studies your application behavior. He knows how often you log on and when; what percentage of white men, black men, Asian men you have chosen; what types of people are interested in you; what words you use most; how much time people spend in your picture before choosing you, etc.” He adds: “Tinder knows a lot more about you when he studies your behavior on the app. Personal data is the engine of the economy. Consumer data is exchanged and negotiated for advertising purposes”.

The idea here is not to critic Tinder but to illustrate our point: dating applications store and transmit huge volumes of personal data. And these data are of particular interest to cybercriminals…

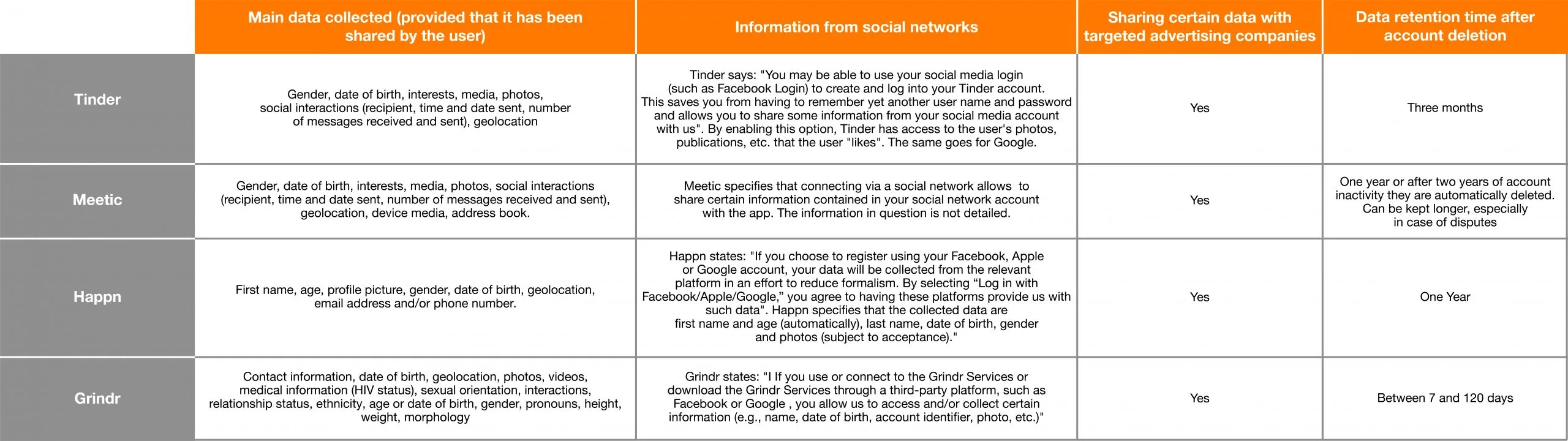

We, therefore, focused our study on the most well-known applications on the market: Tinder, Happn, Meetic, and Grindr.

Meeting apps: what are the cyber risks?

The goals and modus operandi of cybercriminals targeting dating apps can be classified into three categories.

Data theft

The photos of a user, his age, his location, his first name (possibly his surname)… are the data that cybercriminals try to obtain.

To what end? All the work of an attacker is based on obtaining information. He needs to know his target’s tastes, such as intimate details of his life (the name of his pet, for example). With this information, he significantly increases his chances of compromising a mailbox, a Facebook account, or any other medium containing information that is even more interesting.

Once the cybercriminal has this information, he can decide to resell it to the highest bidder or create password dictionaries. These are lists of potential passwords, combining, for example, the name of the pet with a department number.

Moreover, according to a Cyclonis study, the reuse of a password is a common thing. Once an account has been hacked, compromising other accounts is only a matter of time and variations (one number instead of another, a special character instead of another, etc.).

The Feelings Scam

Indeed, there are technical attacks that allow cybercriminals to steal data. These attacks require little investment but also yield relatively little profit… In comparison, the technique is known as “feelings scams” can make it possible to obtain amounts of money exceeding tens of thousands of euros.

The purpose of a feeling scam is to seduce a person for long enough to create a bond of trust. Once this bond is established, for one reason or another (family drama, help for an association, etc.), the malicious person will ask for large sums of money. Once the desired amount is obtained, the person will disappear.

This type of scam is aimed at people who generally have poor computer hygiene and sometimes lack perspective on what may or may not be true on the Internet.

Hacktivism and blackmailing

Cybercriminals may be motivated by an ethical or political cause and use dating sites to pressure or cause a scandal. We could cite the data leak from the Ashley Madison site in 2015, which had the direct consequence of putting personalities from the American political world in turmoil.

Sometimes these are personal vendettas: stolen conversations from dating applications can be sent to co-workers or employers… reputation and jobs at stake.

Dating apps: what protections and best practices?

Protections implemented by applications

The applications try to guarantee user data security while remaining the most efficient in their mission: to promote romantic encounters.

Uploaded images are “anonymized“ meaning that a cybercriminal not registered on a site cannot be traced back to an account just with a photo he would have retrieved. Also, the images are stored as a string of characters preventing an attacker from retrieving them directly.

During various tests, we realized that it was possible to retrieve all profiles, photos, bios, and the names and dates of birth (supposed to remain private) of all profiles, subject to creating an account on an application. Once this information was retrieved, it was possible to recover 70% of the persons’ Instagram and Facebook profiles.

The techniques used are so basic and rudimentary (we will not explain them here to not tempt anyone), it becomes easy for ill-intentioned people to get closer to their victim in one way or another.

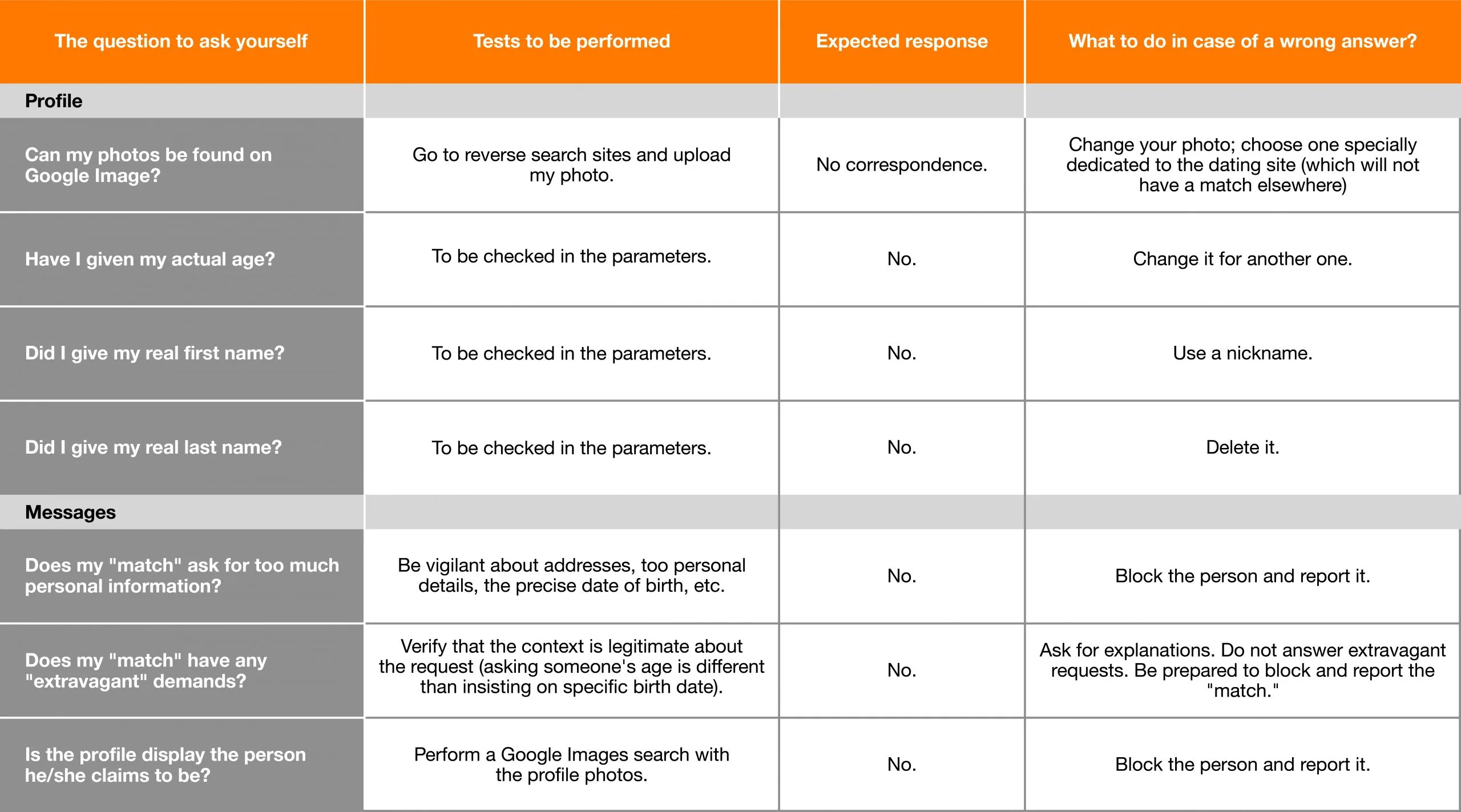

Good practices to adopt as a user

Fortunately, there are simple solutions to protect yourself.

With a few basic security hygiene measures, it is easy to guarantee data security (at least to some extent) and continue to search for your soul mate with peace of mind.

We would like to offer you a small guide in the form of a table. To use it: ask the question on the left and see if the associated answer is close to your practices. If it is very far from it, try to get as close as possible to our answer!