28 June 2022

Authors: Diana Selck-Paulsson & Adam Ridley

This piece is the first part of a series presenting our findings of a qualitative research on ransomware/cyber extortion activities throughout the past two years. It is meant to set the tone on our initial research question, how we went about collecting data and analyzing the research material as well as first high-level, preliminary findings.

We easily use the term ‘criminal’ and/or ‘cyber criminals’ in our (cybersecurity) industry. It's a term that leaves an impression. Sometimes it is sensational when we feel we have something to share that we want others to pay attention to. The term ‘criminal’ can arouse a sense of fear, a fear of something unknown or unknowable, of someone different or ‘other’ than us. We prefer to use the terms 'threat actor', 'offender' or ‘delinquent’ instead. Especially in cyber, we know very little about the deviant individuals or groups of individuals that we might attribute to specific actions or techniques. We might not know for certain in which country they are based in, and which laws apply to them; their victims might be located somewhere completely different and because of the anonymity and the virtual nature of time and space, attribution is difficult. So, for simplicity, let's call them threat actors, offenders or delinquent.

Since early 2020, Orange Cyberdefense has enhanced its research capabilities to better understand the threat of ransomware and cyber extortion. As researchers, we have observed a major change in ‘transparency’ of these activities. Threat actors have decided to publicly name and shame businesses that have fallen victim to ransomware. One byproduct of this strategy is that researchers and others can also see who and how many businesses became victim of such attacks. For the time being, victims are not obliged or mandated to report cyberattacks, and so as a consequence there is no way of knowing how bad the attack really is; no central dataset that shows it all. And of course, even now when some victims are publicly posted online, there are still a number of ‘dark’ victims that we will not know about. However, the number of those victims that are publicly listed are still more than we have ever known up to this point, and gives us a good starting point in researching this threat and its developments.

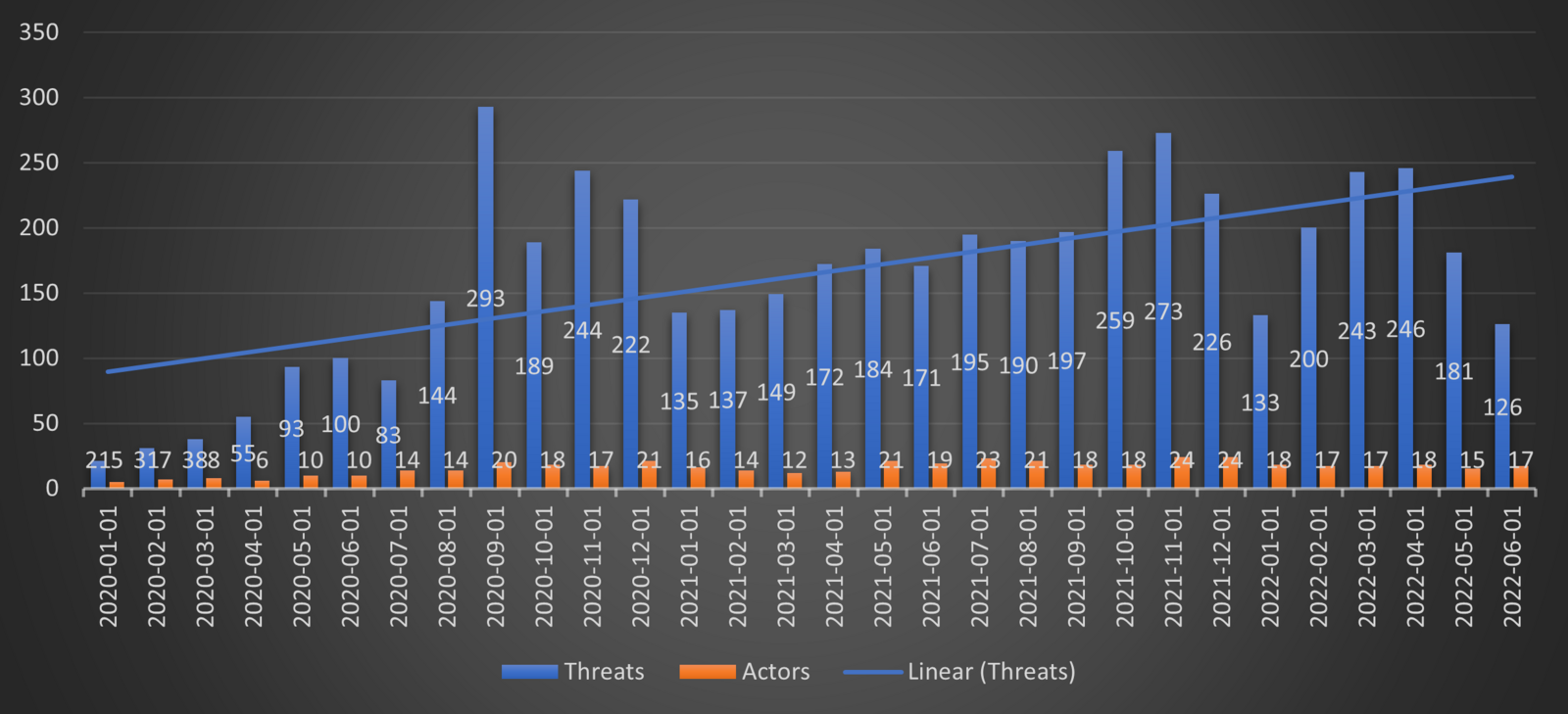

Additionally, threat actors noticed that stealing businesses’ data and using this to extort money can be just as effective as encryption when demanding a ransom payment. As a consequence, over the past two years, some threat actors began to ‘only’ exfiltrate data and use this for extortion. For this reason, we propose naming this threat cyber extortion (Cy-X) instead of ransomware. What we are currently observing is that Cy-X seems to be successful enough for threat actors to continue victimizing businesses around the world by starting their own operations or join existing ones. From our own tracking of cyber extortion victims (called ‘threats’ below in Figure 1) this phenomenon has continued to increase over the past 2 years. Therefore, this is a threat that needs to be taken seriously.

Over the past 18 months we have started a new research project – alongside our continuous data collection tracking the scope of the Cy-X threat – trying to understand and answer one of our most pressing questions:

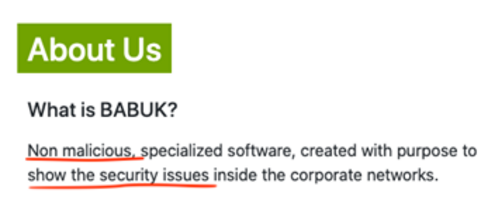

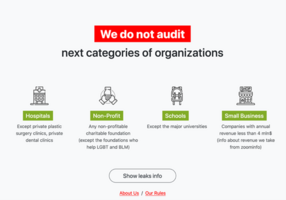

By late 2020 and early 2021, we were observing that threat actors seemed to justify their actions in a language that suggested that they only ‘conduct business’ with their 'clients', 'partners' or 'customers'. Threat actors would describe their deviant behavior as service offerings such as 'auditing' or 'pentesting'. Somehow, these observations didn’t sit well. They didn't offer legitimate business services, they were conducting crime: they attacked businesses around the world and extorted money for it. The communication channels they provided were not 'customer portals', as they would call them, but victim portals. The money is not willingly paid as an exchange for a business service but extorted due to extortion following deviant activities, pressuring the victims into complying to pay the threat actors.

This observation, such as in Screenshot 1, was an interesting one. Besides the business language applied, we would also observe a certain ‘tone’ of arguing or justifying their deviant behavior for the cause of the greater good, such as pointing out bad practices in network security or overall bad cyber security and information security practices of their victims. Below is an excerpt from Maze explaining the rationale for their criminal behavior back in 2020.

“There are a lot of rumors, lies and speculations around our project. So we decided to answer the question “why” and “what for”.

Why? Our world is sinking in the recklessness and indifference, in laziness and stupidity. If you are taking the responsibility for other people money and personal data then try to keep it secure. Until you do that there will be more projects like Maze to remind you about secure data storage.”

- Maze press release, November 2020

Between February 2021 and February 2022, we started to collect negotiation chat conversations, press releases, announcements and opinionated paragraphs from the leak sites. The data collection resulted in 232 unique content pieces of 11 different types.

About Us | 10 |

|---|---|

Announcement | 34 |

Cyber insurance | 1 |

Forum Post | 2 |

Internal Chat | 1 |

Interview | 10 |

Leak Page | 47 |

Logo | 4 |

Negotiation Chat | 76 |

Ransom Note | 32 |

Victim Portal | 14 |

Total: 11 Types | 232 |

Table 1: Summary of collected qualitative research material

The research material was collected from 35 different threat actor groups that have in the past or currently still are exercising cyber extortion and maintain a leak site on the dark web to name and shame their victims. One exception is Ryuk, who maintains no leak site to our knowledge. The collected material is of qualitative nature and this provides contextual data that has been publicly expressed by the threat actors. Consequently, one limitation is that said threat actors are shaping the narrative we have analyzed and thus we recognize a certain subjectivity of its contents. On the other hand, negotiation chats between the offenders and victims were originally meant to be private but through mishandling by individuals of the victim organization, instructions on how to access the communication channels ended up on publicly available websites. Additionally, we want to express that this dataset is in no way meant to be representative, there are negotiations between threat actors that remained private and inaccessible. Nevertheless, we do consider the content of the negotiations and from the other sources as insightful and useful for investigating the way offenders justify their actions.

In order to analyze the collected material, we chose to apply a criminological theory to the material. By applying a multi-disciplinary approach, a crime theory to the phenomena of cyber extortion and ransomware, we are hoping to gain a better understanding of this threat and help answer our initial question on whether or not threat actors are aware that their actions are deviant or criminal.

In 1957, Sykes and Matza established the five techniques of neutralization, a theoretical approach to understand delinquency. In their observations, they opposed the idea that delinquents would learn their deviant behavior through sub-cultures, learning (anti-)social behavior and values in the process of social interaction as their new alternative set of norms. Instead, they noticed that delinquents would still show guilt or remorse and thus argued that delinquents would come up with ‘extensions of defences to crimes in the form of justifications for deviance’. These justifications would then enable the offender to ‘drift’ away from the socially accepted norms and values and partake in delinquent behavior. This does not mean that offenders reject social norms of society entirely but that through techniques of neutralization they would then rationalize themselves away from the moral restraints, and thus social control. This would happen prior to their involvement in criminal activity, enabling them to engage in crime while in their own understanding they would remain nondeviant.

Five different types of technique were recognized by Sykes and Matza, and are well understood and established in criminology today, including in the digital context (Brewer et al., 2020):

Denial for responsibility could simply be argued that the deviant behavior was an accident, and thus the delinquent is negating personal accountability. It could also be argued that outside forces contributed to the behavior and thus circumstances are blamed.

Denial of injury is the question of whether or not someone has actually been hurt, but this becomes difficult to determine in cyberspace. Harm might not be as ‘visible’. It could be argued that the victim well-deserved it.

Denial of the victim might be one of the most applicable techniques when researching cybercrime according to Brewer et al. (2020). Since cybercrime can sometimes appear victimless, the likelihood to engage in crime by using this neutralization technique is very present. It can also be argued that the injury is not really an injury but a rightful retaliation or punishment. As Sykes and Matza (1957) state, ‘by a subtle alchemy the delinquent moves him- self into the position of an avenger.’

Appealing to higher loyalties means that delinquents would sacrifices their law-abiding values of society for the values of a smaller social group. It could also be interpreted as ‘helping society’ and showing loyalty sub-groups such as hacker communities (Chua and Holt, 2016). This means that individuals do not reject social norms and values generally but potentially show higher loyalty to norms that belong to their social sub-group.

Condemning the condemners is the last of the five neutralization techniques and describes when offenders try to shift the focus of attention from their deviant behavior to motives and behavior of the ones that disapprove (authorities, parents, teachers etc.).

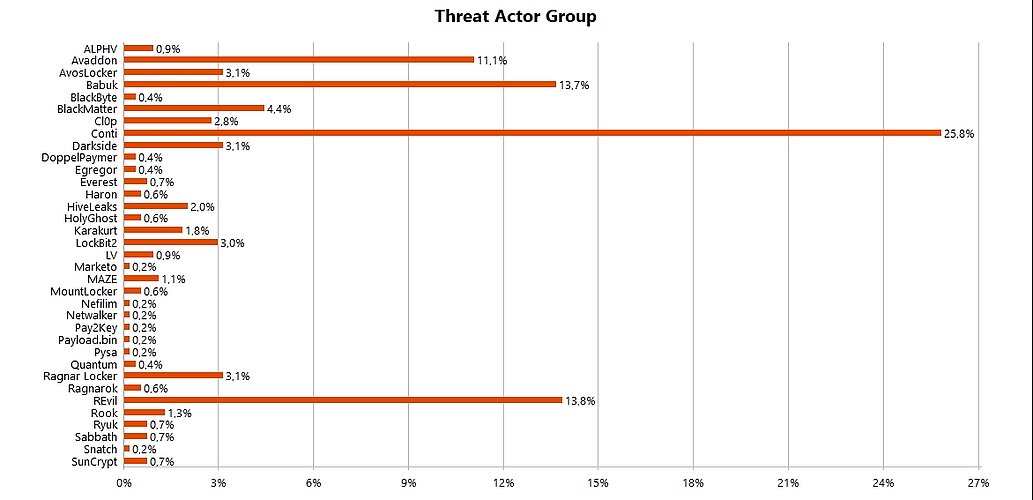

The collected research material (n=232) is distributed as follows. We collected most of the research material from Conti negotiation chats and other sources (26%), followed by REvil (14%), Babuk (14%), Avaddon (11%) and BlackMatter (4%) as the top 5 threat actor groups with the highest amount of material to analyze (see Figure 2).

One of our main focuses was to analyze whether or not we could identify one or several of the five neutralization techniques actively applied by the threat actors in their negotiations with victim organizations. We also wanted to see if there was evidence of these techniques in threat actors’ communication to the public.

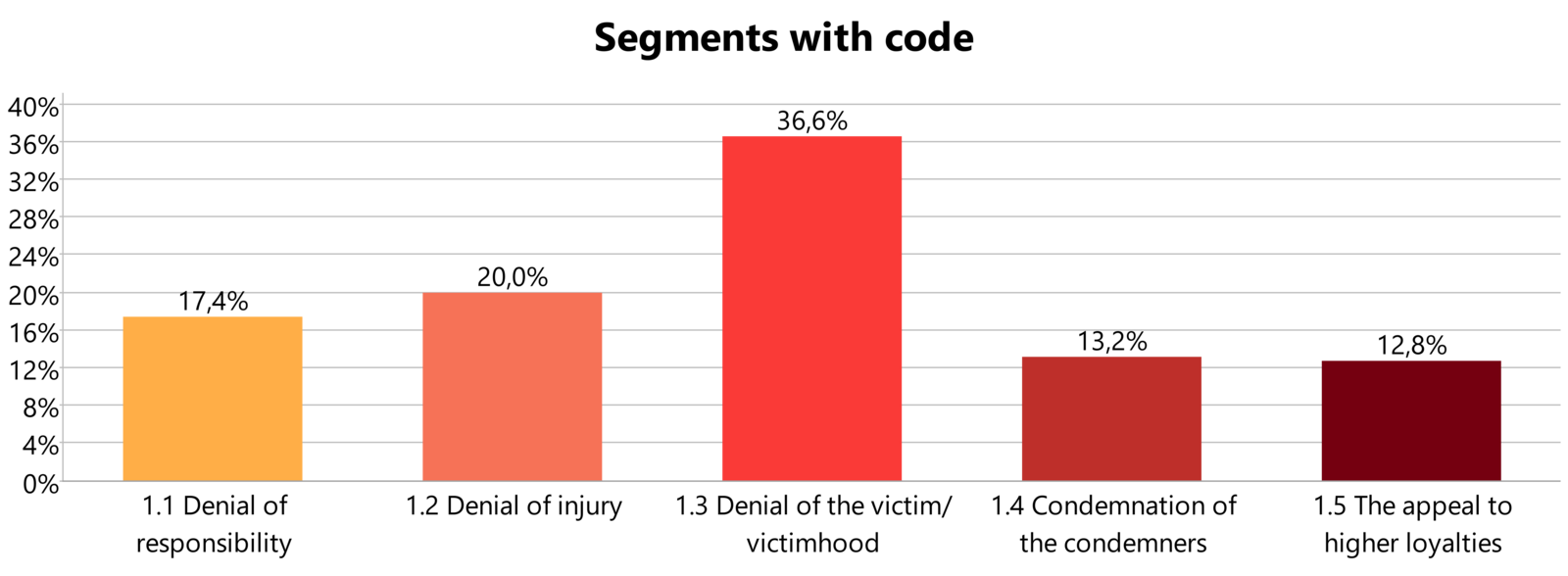

As a preliminary result, we found that all five neutralization techniques were present in the threat actors’ communication to justify their deviant actions of conducting crime of extortion (see Figure 3). We added one sub-technique called ‘Denial of injury – imitation of business language’ under the neutralization technique ‘Denial of injury’. This code was applied whenever threat actors would use business language when describing or communicating with their victims. For example referring to their victims as ‘clients’ or ‘partners’.

Overall, our initial findings show that the neutralization technique ‘Denial of the victim’ is used the most as shown in Figure 3, and thus goes in line with previous research findings from Brewer et al. One reason for this is most likely that deviant behavior in cyberspace can often seem victimless due to the physical distance between offender and victim.

As we argued previously this technique also includes rationalizing deviant activities in a way that it’s the victim’s fault by viewing these actions as retaliation or punishment that was rightfully done.

“Just one other law firm collecting big fees yet forgetting to protect personal information of clients. Here we have some very corrupt bunch of players who thought to threaten us so really are looking to hide what some interesting cases that are border on corrupt exist in their documents.” - Cl0p

Another aspect of this technique is the role the offender takes. In 1957, Sykes and Matza described that delinquents would view their role similar to Robin Hood, a figure displayed as a tough detective seeking justice outside the law.

In 2021, we see threat actors exercising cyber extortion viewing themselves as exactly that:

“This time we will be in the role of Robin Hoods. Today we will give light to the world on a company that does very bad things.” - Avaddon

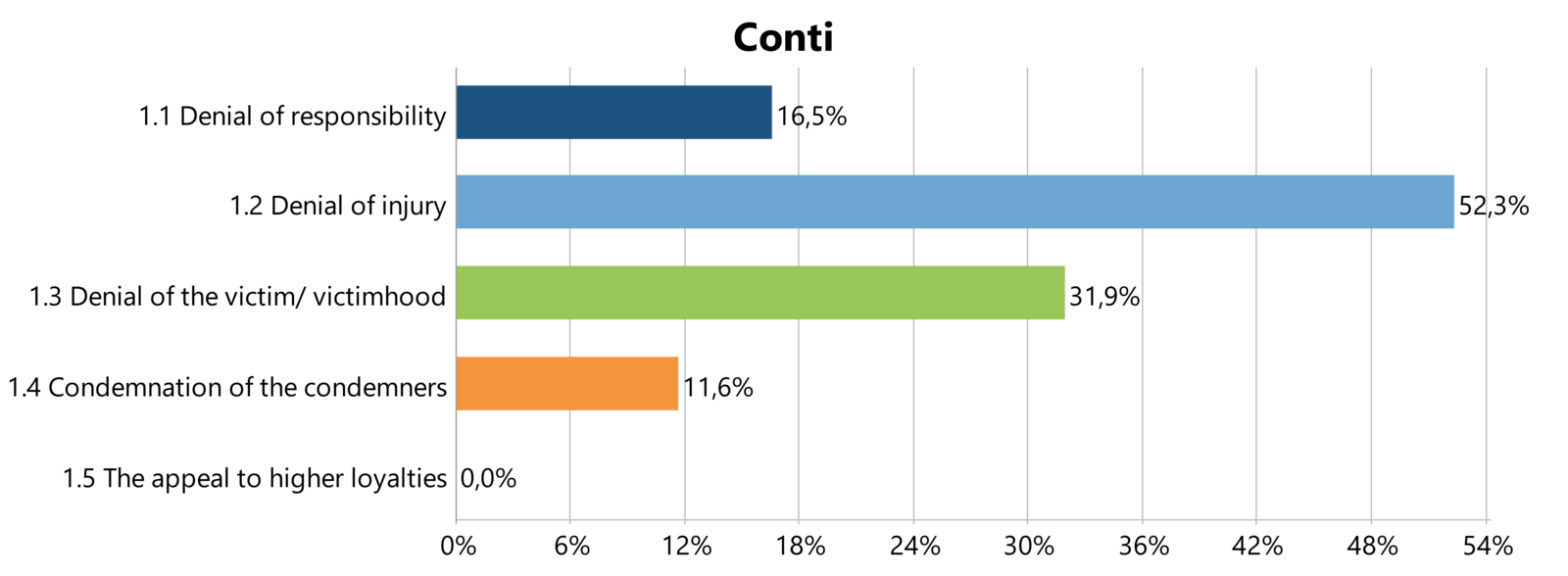

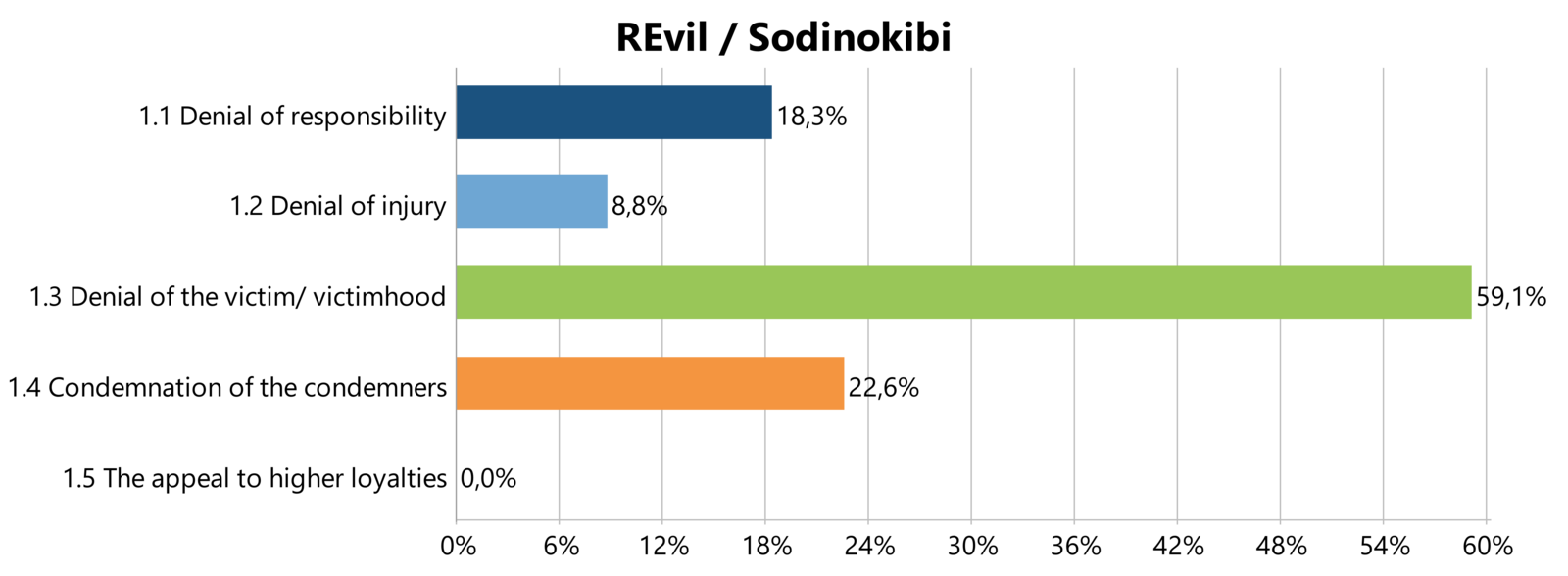

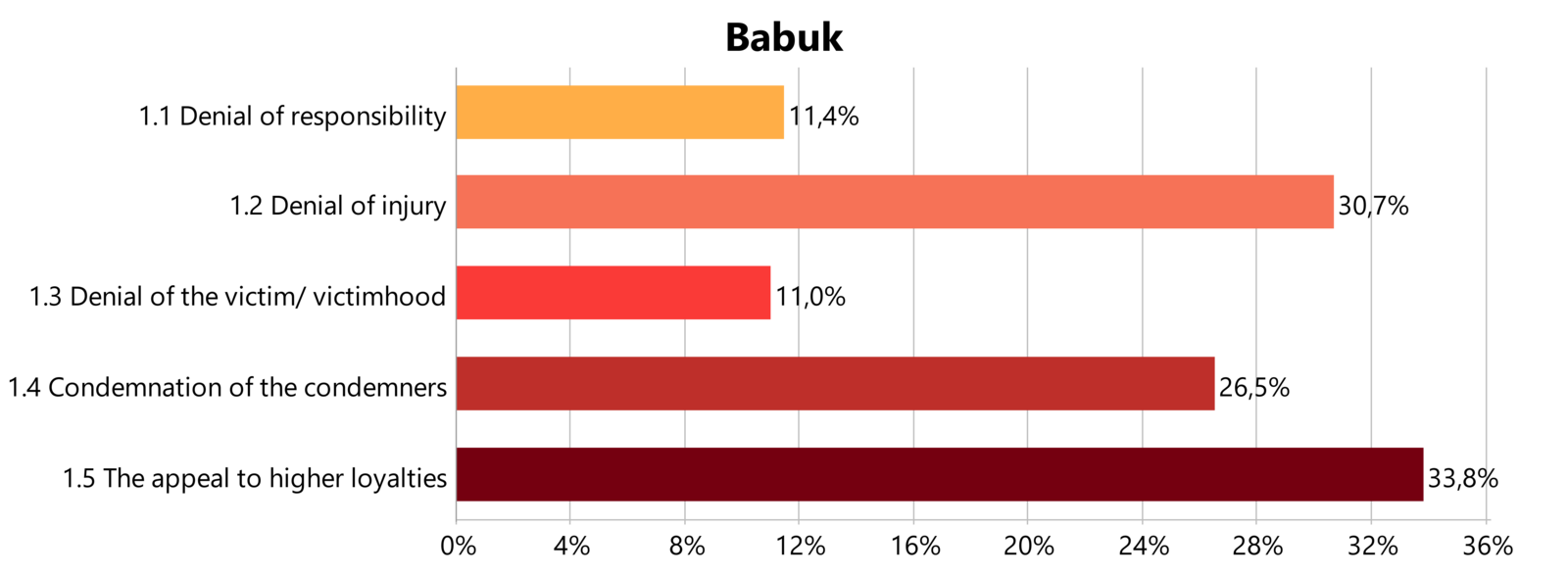

If we then look at the three threat actor groups we have collected the most research material from, namely Conti, REvil and BABUK; we can see the following neutralization techniques applied (see Figure 4-5-6).

As a conclusion, the three threat actor groups vary greatly in the techniques they have applied in order to justify their engagement in crime. While Conti does not recognize the harm done by their actions, followed by the failure to acknowledge the victims being actual victims, REvil mostly denies the victimhood of organizations that fall victim to them, while BABUK members applied two justifications almost equally. They are also denying that harm has been done through their actions, as well as justifying their deviance by appealing to other norms and values that are not the law abiding values of society.

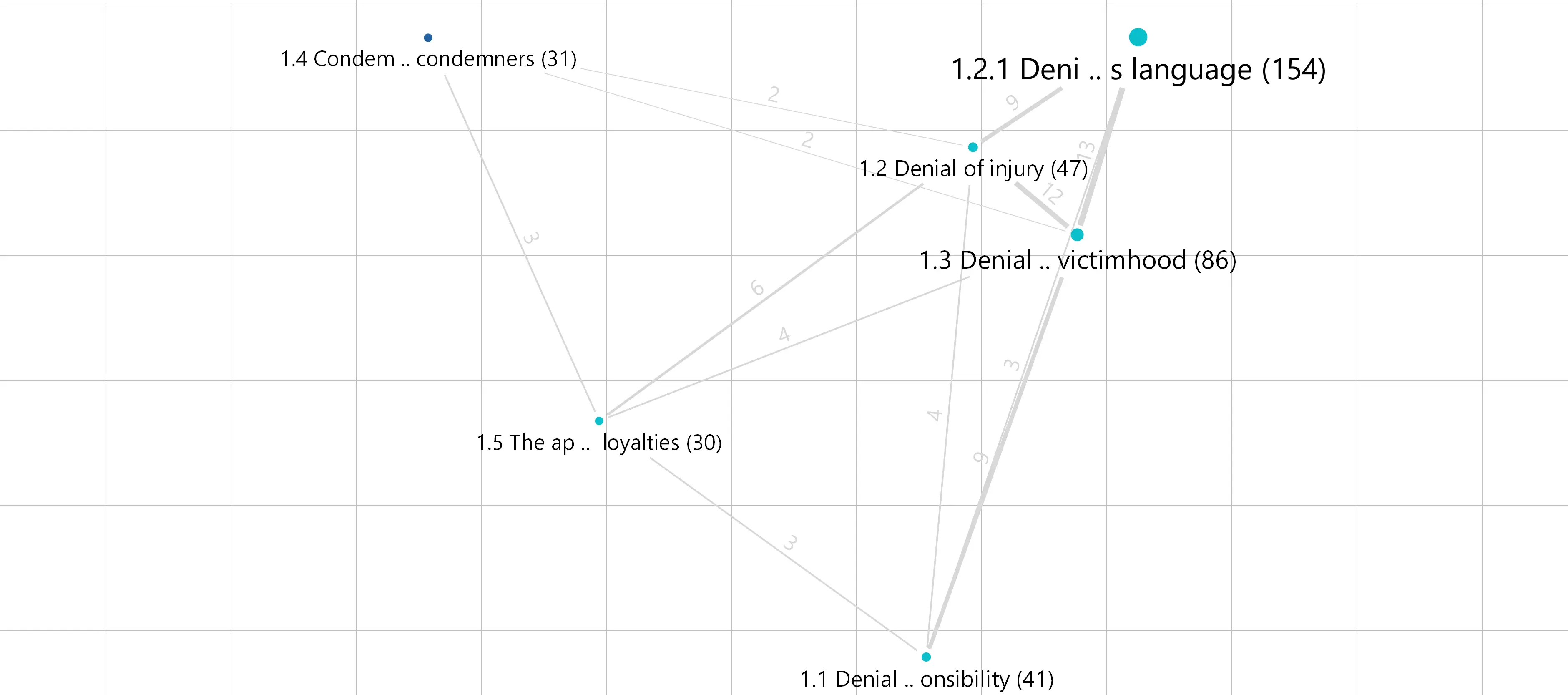

Similar to the literature on applying neutralization techniques to engage in crime, we also found that the two techniques ‘Denial of injury’ and ‘Denial of the victims’ are very close to each other. In a way this makes sense, if a threat actor does not see the victim as a victim but a ‘client’ as in our case; recognizing a harm done and thus an injury will be equally rationalized away (as can be seen in Figure 7).

This write-up is meant to introduce you to our research and provide you with our preliminary findings. We posed the question whether or not threat actors know deep down that their actions are deviant. Our findings show that we did observe threat actors applying a multitude of combinations of the five neutralization techniques introduced by Sykes and Matza. This enables threat actors to ‘make’ delinquency permissible. Often this does not indicate that offenders live by these deviant norms and values for life, but instead, that they have found a way, namely rationalizing or justifying their actions in order to ‘drift’ and thus engage in criminal activities temporarily.

The most frequently applied technique was denial of injury, when including the sub-technique ‘denial of injury – imitation of business language'. This suggests that threat actors have spun a narrative around themselves that may help them to justify their deviant behavior into something more acceptable, namely ‘conducting business’. By denying injury, offenders fail to see the harm they have caused. This is especially true in the digital context, in which anonymity and the spatial distance between victim and offender can enable this denial effectively.

If anything, offenders seem to blame the victim for the damage, arguing that the victims could have prevented this if they would have implemented better cyber security practices and by that removing the victim’s victimhood. In the material that we coded as ‘Denial of victimhood’ we would find justifications that go in line with the pre-existing literature, displaying their actions as ‘rightful retaliation’ in response to the wrong-doing of the victim, consequently viewing themselves as a Robin Hood-like figure. Alternatively, some threat actors would argue that the victim could well afford the retaliation and in some cases would even benefit from it. That is to say, not fall victim to other cyber extortion ‘competitors’.

“Fortunately, Conti is here to prevent any further damages! First, we can provide you with IT support by offering a decryption tool, as well as a security report that will address the initial issues with your network security that resulted in this situation. Secondly, we offer you damage prevention services.” -Conti, denial of the victim