28 June 2022

In our recently published Security Navigator report we highlight the fact that ransomware operations involving data encryption have been increasingly coupled with extortion tactics from threat actors to further pressure victim organizations into paying ransoms. This is what we term cyber-extortion (Cy-X). This trend is key when looking at the current threat landscape. Indeed, most of the currently active ransomware operations perform double-extortion (or even triple-extortion), for instance threatening to leak stolen information on the Dark Web or to sell it to the highest bidder if the ransom is not paid or launching DDoS attacks against the same victim.

Extortion in itself has thus arisen to a point where encryption is not always necessary: it is equally lucrative to hack and leak an organization. This shift in cybercrime operations partially results from the overall improvement by organizations of their backup strategies in order to better prevent ransomware attacks, leading some threat actors to now only perform this type of operations. This is for instance the case of groups such as Karakurt, RansomHouse or Silent Ransom…

Double extortion is all the more problematic as leaked information can facilitate further compromises from other threat groups. These leaks feed the ongoing data trade within underground marketplaces and cybercriminal forums.

Until the fundamental systemic factors that enable this form of crimes are addressed, we should expect to see criminals continuing to adapt and test new pressure tactics to rush victims into paying exorbitant ransoms. We continue to see Cy-X groups come and go, primarily because of how lucrative these extortion operations appear to be, along with their apparent ease of execution and supposed anonymity. Even if law enforcement agencies sometimes succeed in identifying and arresting members of these clusters, this often leads to groups disbanding, rebranding and updating their tactics to further avoid detection.

This leads us nicely to a new ransomware group known as PLAY, which leverages double extortion through its own leak site.

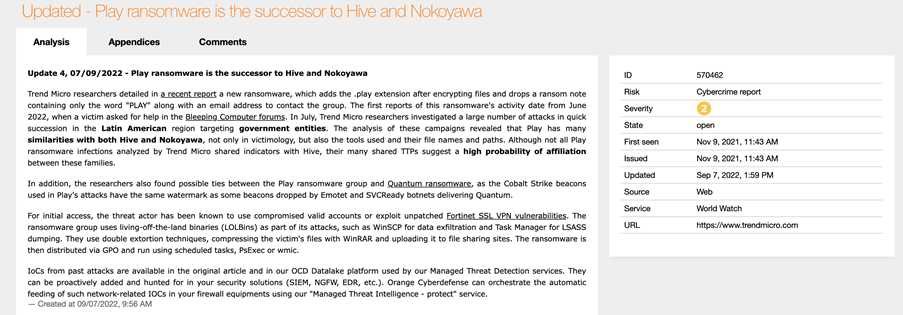

We first notified customers of the threat presented by PLAY in a CERT ‘World Watch’ advisory published in early September 2022 (https://portal.cert.orangecyberdefense.com/worldwatch/570462 for registered users).

“Trend Micro researchers detailed in a recent report a new ransomware, which adds the .play extension after encrypting files and drops a ransom note containing only the word "PLAY" along with an email address to contact the group. The first reports of this ransomware's activity date from June 2022, when a victim asked for help in the Bleeping Computer forums. In July, Trend Micro researchers investigated a large number of attacks in quick succession in the Latin American region targeting government entities.

For initial access, the threat actor has been known to use compromised valid accounts or exploit unpatched Fortinet SSL VPN vulnerabilities. The ransomware group uses living-off-the-land binaries (LOLBins) as part of its attacks, such as WinSCP for data exfiltration and Task Manager for LSASS dumping. They use double extortion techniques, compressing the victim's files with WinRAR and uploading it to file sharing sites. The ransomware is then distributed via GPO and run using scheduled tasks, PsExec or wmic….”

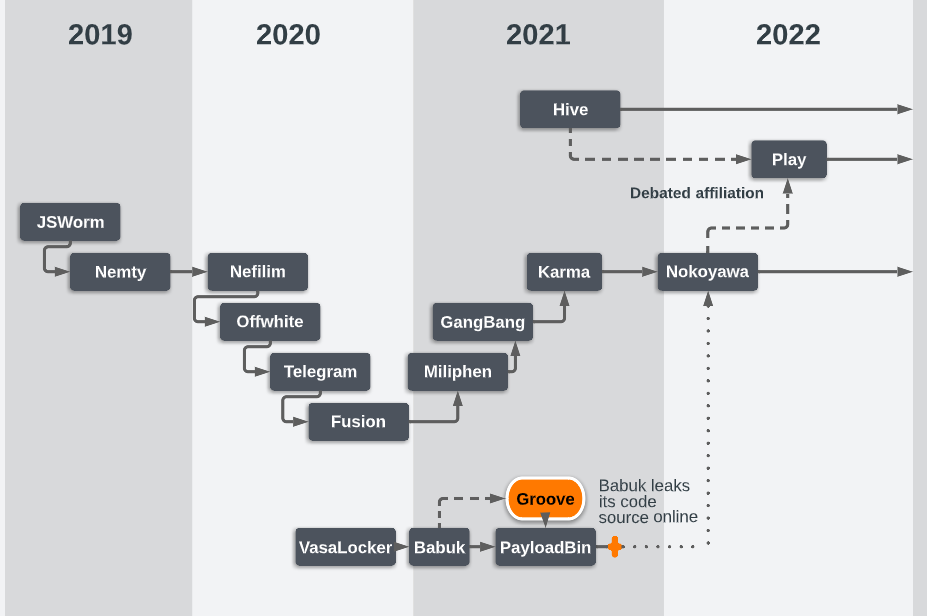

The threat cluster behind PLAY is yet to be extensively covered by security researchers. Trend Micro was the first vendor to publicly document this threat actor in a report[1] published in September 2022, where they provided analysis following investigations into attacks carried out in July. Based on their analysis they believed that PLAY was the successor of Hive, a notorious ransomware active since 2021. It also shares some overlaps with Nokoyawa, yet another ransomware operation. However, there is nothing concrete that allows us to assess with high confidence whether PLAY is definitely a successor of one of these two ransomware families.

In early September, security researcher Chuong Dong also published a technical analysis of the ransomware being used by PLAY, focusing mostly on its anti-analysis and encryption features. In his blog post[2] he states that PLAY is heavily obfuscated with a lot of unique tricks that have not been used by any other ransomware.

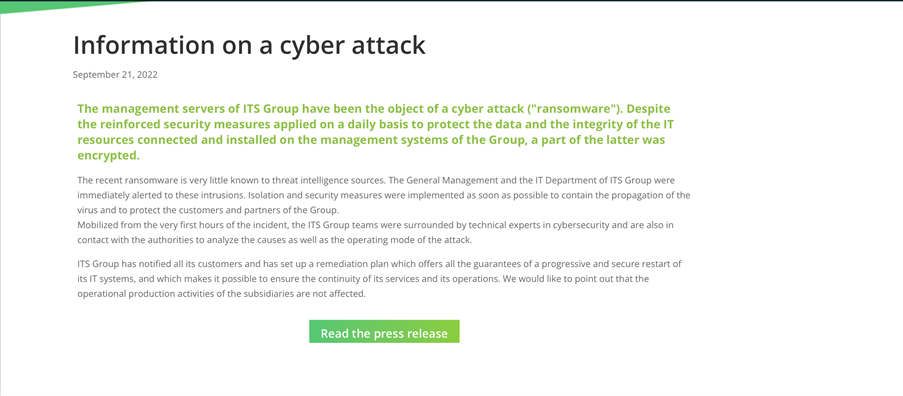

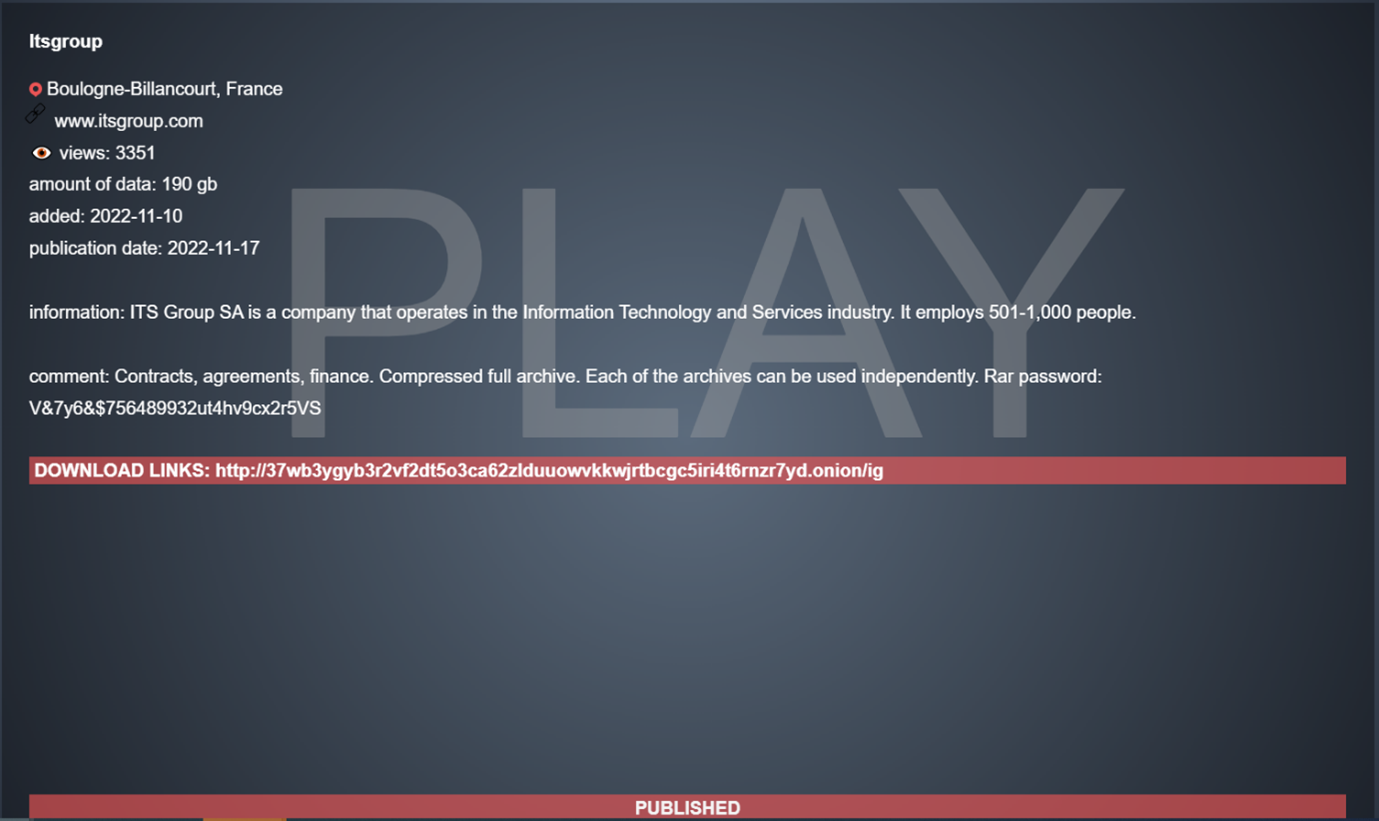

One of the first victim was the French ITS Group, who disclosed the breach via their website:

Since November 2022, our CERT started investigating a surge in PLAY compromises.

Recently our friends at CrowdStrike reported the exploit dubbed OWASSRF while investigating Play ransomware attacks, where compromised Microsoft Exchange servers were used to infiltrate the victims' networks. OWASSRF is a chaining of CVE-2022-41080 and CVE-2022-41082. PLAY has also been reported to exploit ‘ProxyNotShell’ (CVE-2022-41040), but CrowdStrike found that the flaw abused by a newly discovered exploit is likely CVE-2022-41080, a security flaw that allows remote privilege escalation on Exchange servers[1] which Microsoft tagged as critical but not exploited in the wild when patching it last November.

We searched for these three vulnerabilities in a significantly sized sample of our Vulnerability Scanning clients and only found occurrences at 2.5% of the clients we examined. Only CVE-2022-41040 and CVE-2022-41082 were found together at the same client, and we found that occurence only once.

This of course does not reduce the significance of these vulnerabilities, which are clearly being exploited in the wild, but it is encouraging to see that they are apparently being successfully fixed by most of our client base.

In a recent, common practice amongst other Cy-X groups, PLAY ransomware recently published a website, accessible only through Tor, where the group is disclosing details about victims and leaking stolen data if the victim doesn't pay the ransom. The ransom note left by PLAY used to be very blunt and specific to the victim with only an email address to contact the threat group. Usually though, ransomware operators take the time to explain to the victim how to acquire the requested cryptocurrency and threaten retaliation if they contact recovery companies or law enforcement. This guidance is nevertheless being provided by PLAY in the FAQ section of this newly published data leak site. The group behind PLAY are also following a recent trend among ransomware operators whereby they apply additional pressure on victims during negotiations by initially obfuscating the victim's name on the leak site, thus giving them an opportunity to pay in order to prevent their full name from being released publicly.

The ‘added’ date on the leak below is deceiving, because PLAY actually carried out this compromise before the launch of their site. The compromise likely dated back to September.

Unsurprisingly, our Computer Incident Responses Teams (CSIRT) has encountered this threat group in three different cases in the last month.

We held a call with one infected customer at 09h00 the morning after their systems were encrypted in November. Investigations commenced immediately and by 12h20 our team was processing evidence.

The customer in question is not a large business. The initial point of entry appeared to be VPN access using legitimate credentials, and the ransomware deployment and encryption had taken place over the course of just one day. On some machines malware was deployed and triggered manually via RDP, on others it was via PSExec. Almost the entire environment was encrypted. Onsite backups were either encrypted or destroyed. Fortunately for this victim, a set off reliable off-site backups allowed us to recover most of the data and systems. Unfortunately for this victim, several hundred gigabytes of data were published on the PLAY data leak site.

Our CSIRT worked over a period of 8 days to assist and proceed to identify, track and contain the compromise. A malware sample that proved to be PLAY was discovered early on, and forwarded to our CERT (Computer Emergency Response Team) to identify the strain and capabilities of the code, using the sandbox described below.

Our experience across these cases leads us to suspect that we are dealing with a separate PLAY affiliate, perhaps specializing in Europe. The IoC and TTPs identified in all three cases overlap considerably, and in two other cases in France we’re aware of (but didn’t work on directly) we believe the sample of the remote access tool ‘systemBC’ recovered was identical. Yet none of the intelligence we collected from the three cases we’ve worked on so far overlaps with intelligence we’ve received from third parties working on cases elsewhere.

Some of this infrastructure is still active and located in Europe, so some IoCs can be share only once French or European law enforcement have been involved properly. Some are nevertheless provided at the end of this report.

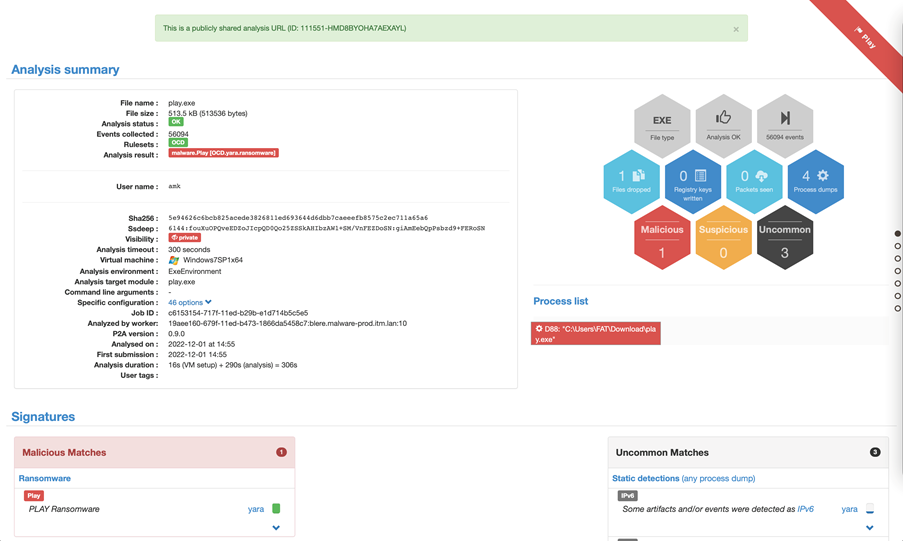

The first step for our Reverse Engineers was to determine the malware family, easily obtainable with the .play encrypted extension.

The suspicious executable found on the system was detonated in our proprietary ‘P2A’ Sandbox to discover the attributes and behaviors of the file. We confirmed the family thanks to a custom ‘YARA’ rule stemming from our World Watch advisory and automatically embedded in P2A. This rule can be used to search for PLAY files elsewhere in ‘live’ environments. As a reminder, YARA is an open-source tool designed to help malware researchers identify and classify malware samples. It makes it possible to create descriptions (or rules) for malware families based on textual and/or binary patterns.

Our SaaS file analysis sandbox, P2A, can be used to easily confirm whether suspicious files belong to one malware family. Fortunately, our sandbox allows for any analysis to be shared publicly, so you can view this output directly here: p2a.cert.orangecyberdefense.com/analysis/111551/publicshared/HMD8BYOHA7AEXAYL

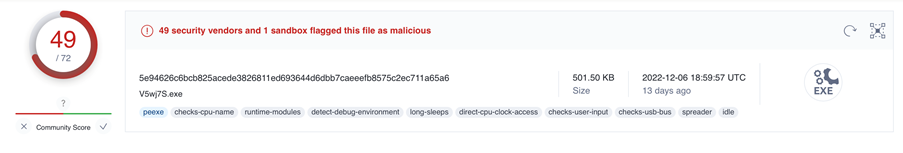

The YARA rule we created then triggered an alert on VirusTotal’s ‘LiveHunt’ service (https://support.virustotal.com/hc/en-us/articles/360001315437-Livehunt#h_b063a6e6-6de5-4aea-ab55-9d8ea46fbeb0). Livehunt allows you to hook into the stream of files analyzed by VirusTotal and get notified whenever one of them matches a certain rule written in the YARA language. By applying YARA rules to the files analyzed by VirusTotal we are able to get a constant flow of malware samples of this family, including ones not detected by antivirus engines. The match against our rule from LiveHunt confirmed our initial assessment that we were dealing with PLAY.

Manual reverse engineering of the sample started on November 22nd. The process proved to be challenging and required a full two-days of effort from an experienced engineer, who was able to confirm that the obfuscation techniques observed those described in the analysis by Chuong Dong we mentioned above:

https://chuongdong.com/reverse%20engineering/2022/09/03/PLAYRansomware/

Samples of the malware incorporate an obfuscation technique known as "Return Oriented Programming" (ROP) and garbage code insertion to make analysis more difficult. Other techniques used by PLAY ransomware include string obfuscation and import hashing using the xxhash32 algorithm. It is highly likely that these obfuscation techniques have been recently added to the malware but the code itself remains the same.

Following on from the three cases our CSIRT is engaged in, our Threat Intelligence teams will soon publish an update of our World Watch advisory outlining PLAY’s recent activity.

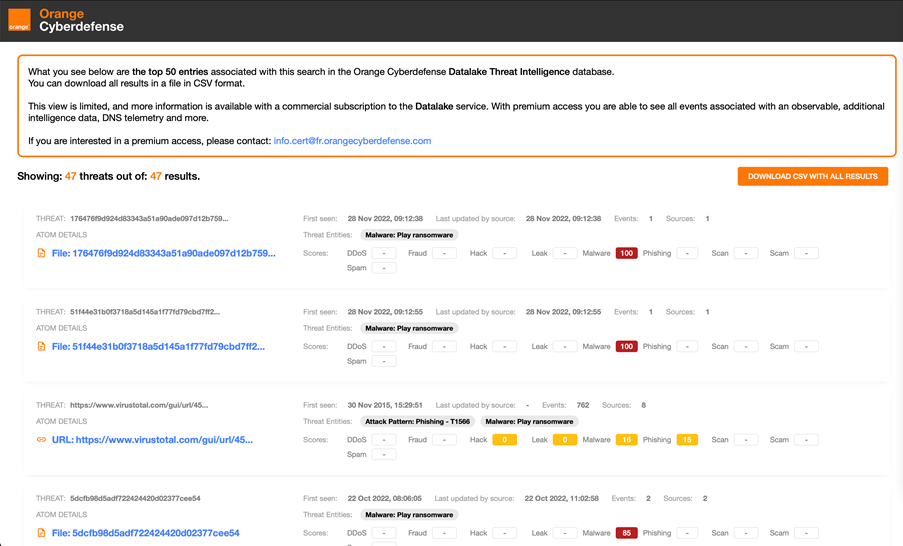

Furthermore, our CERT has also now made publicly available a subset of the PLAY ransomware IoCs contained in our Datalake Threat Intelligence database[3] (available as a SaaS service named Managed Threat Intelligence-detect). As with our P2A sandbox, we are able to share outputs from our database directly with our community, and made these IoCs available for you here (updated once per day only):

datalake.cert.orangecyberdefense.com/api/v2/mrti/public/export-html/

These IoCs are used automatically by our Managed Threat Detection services. You can add them also in your security detection solutions (SIEM, NDR, EDR, etc.), in order to alert your SOC team. Orange Cyberdefense can orchestrate for you the automatic feeding of such network-related IOCs in your security protection equipments (i.e. in various NGFW) using our "Managed Threat Intelligence - protect" service.

28 June 2022

Webcast: Discussing Cy-Xplorer, the #1 cyber extortion report

Webcast: Discussing Cy-Xplorer, the #1 cyber extortion report

8th of Jun

28 April 2023