In the eye of our CyberSOC: Analysis of the Qealler malware campaign

The attacker behind the Qealler malware campaigns seems to have evolved his attacking techniques.

Qealler: more and more campaigns

For several months, Orange Cyberdefense’s CyberSOC has been tracking and detecting malware campaigns aimed at distributing a java-encoded, Stealer-type malware called Qealler. TTPs suggest that these campaigns are orchestrated by the same attacker or group. Over the past several weeks, we have seen an increase in activity: the campaigns are getting closer and closer together and the number and type of companies targeted is growing. Our team’s analysis sheds light on this relatively unknown malware.

Malspam : details of the attack

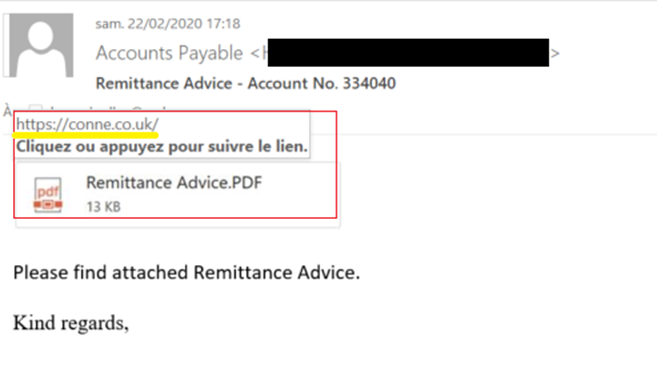

The method of distribution is through e-mails containing an attachment that is supposed to be a PDF document to the victims. We note that the attachment is actually an image (PDF logo) with a hyperlink to the malware.

In the majority of cases, we find the following patterns:

- Le headerFrom Smtp commence par “Account <” ou “Account Payable <“

- The subject always contains “Remittance” usually accompanied by the patterns “Advice” or “Account” with a sequence of numbers (a false reference).

- The email is written in English.

A link redirecting to the attachment (in this case hxxps://conne.co[.]uk)

Figure 1: Example of malicious email – Orange Cyberdefense CyberSOC source

Note that the message comes from a legitimate email address whose account has most likely been compromised beforehand by the attacker. In all cases observed, it is systematically Microsoft Office 365 email addresses.

Each email is addressed to a very restricted list of targets (1 to 5 people maximum). To make his attack more massive and targeted, the attacker uses many email addresses from different sources. As mentioned, these addresses are linked to existing companies and probably to usurped accounts. Through the analysis of SMTP headers, it was also possible to trace some IP addresses used by the attacker to send these email campaigns. These are addresses belonging to hosters. It seems that these IPs are connected to servers that were probably compromised by the attacker.

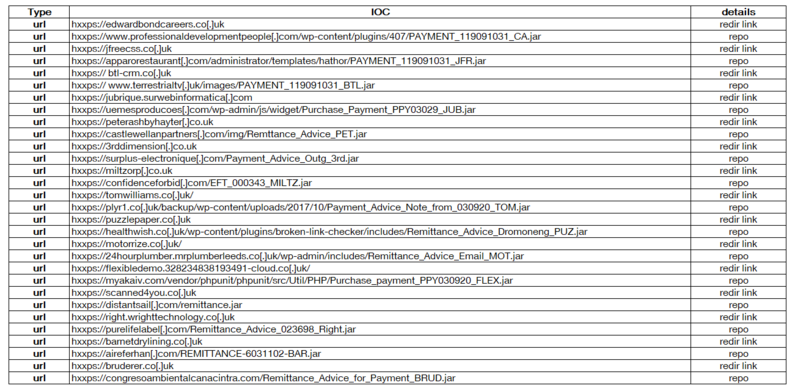

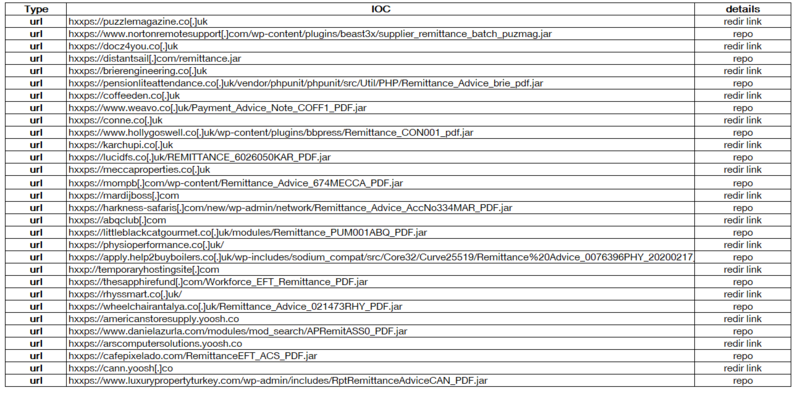

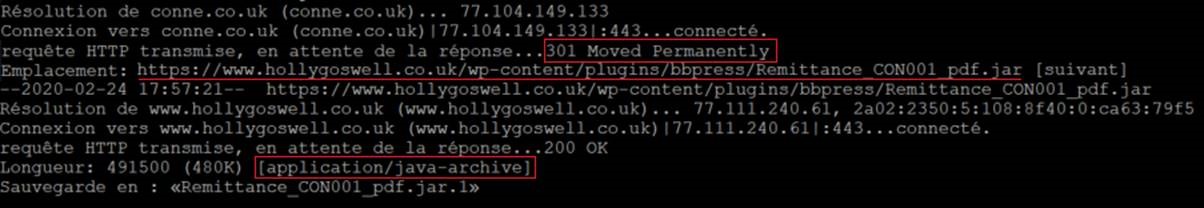

The link leads to a permanent URL redirection (http 301), which redirects to the site hosting the payload. These are very often compromised wordpress sites on which the attacker has deposited his payload, thus acting as a repository. The URL is easily identifiable because it systematically contains the word “Remittance” and ends with “_pdf.jar” or “_PDF.jar”. Note however that this nomenclature has not been respected during the last campaign.

To maximize his chances of success, the attacker uses on average for each campaign a dozen redirection sites and as many repository sites

Qealler: technical analysis

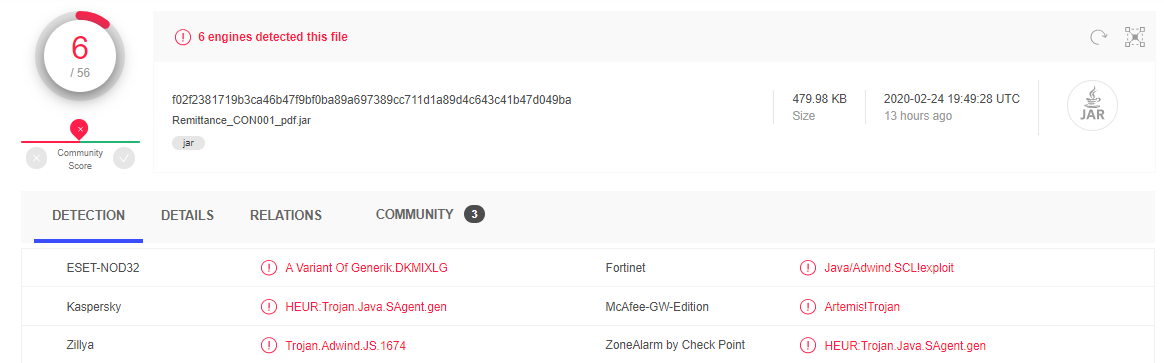

Qealler, also known as Pyrogenic, is a Stealer-type malware written in Java. The first traces of this malware are referenced around August 2018 (VirusTotal).

Several articles presenting this malware have been published in early 2019 by CyberArk and Zscaler. As presented in these articles, the malware is still poorly detected by most antivirus programs. Moreover, the functioning of the latter has evolved since the writing of these articles.

The Zscaler article covers the so-called “reloaded” version of the malware. The current version (V4) contains several evolutions. While the malware is still heavily obfuscated, we note that network flows are fully encrypted. Moreover, in the version covered by Zscaler, the malware uses QaZagne, a fork of the python project LaZagne, to steal credentials. This is no longer the case in current campaigns.

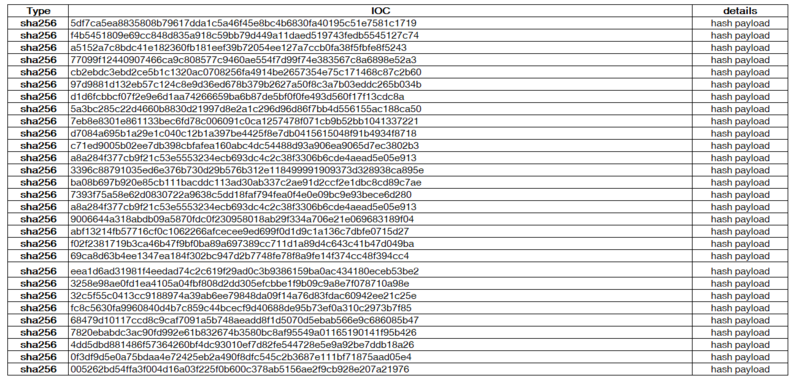

The studied payload f02f2381719b3ca46b47f9bf0ba89a697389cc711d1a89d4c643c41b47d049ba is a jar archive containing a large number of resources. There are 469 classes and 233 miscellaneous files (.7z, .csv, . so, . txt etc). Contrary to what their extensions suggest, these files are actually encrypted.

The jar archive behaves like a loader. In short, at runtime, it will decrypt part of the encrypted data contained in the archive, thus obtaining code that will allow the loader to contact its C2. Once the contact is established, it will recover the code allowing to exfiltrate the credentials.

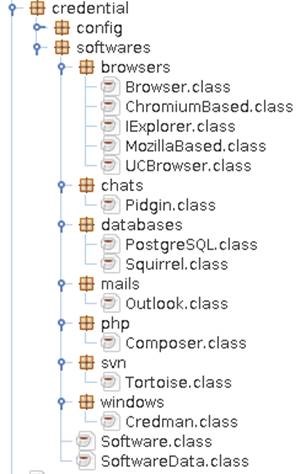

This malware is notably able to steal Windows credentials (System and Outlook), those stored in most web browsers (Chrome and derivatives, Firefox and derivatives, IE) as well as access credentials to certain databases and development tools. The malware contains a class for each source of credentials it seeks to steal.

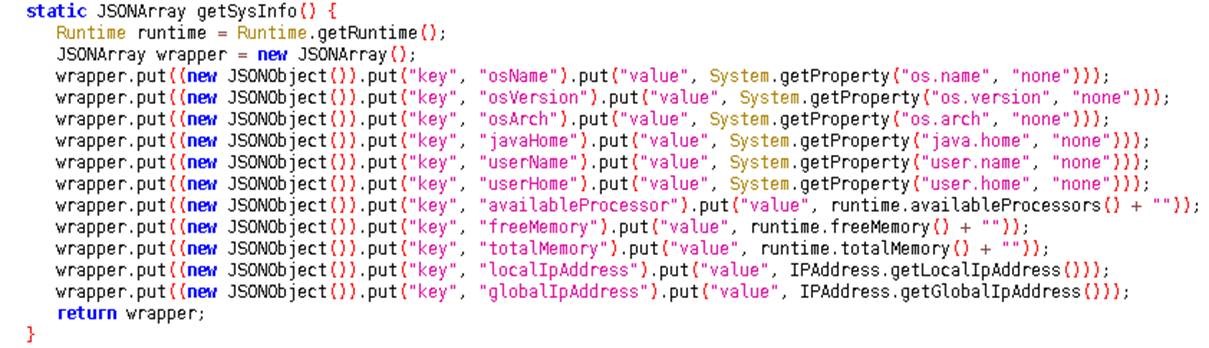

We also notice that the malware will exfiltrate information about the system such as OS version, public and private IP address etc.

Qealler detection

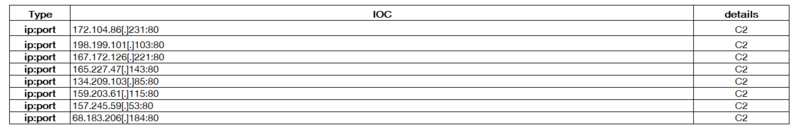

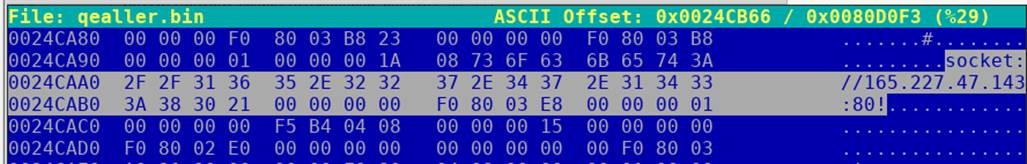

In terms of its behavior, we notice that it connects to the IP address of C2 (specified statically in the malware code). So it does not perform a DNS query. It connects to the C2 directly by IP on port 80. Note that via the malware execution reports in the sandbox, it is easy to identify the C2. However, it is still important to analyze the malware in more detail because it may contain another C2 serving as a backup.

We also note that the malware makes a request to bot.whatismyipaddress.com to obtain the public IP of the infected machine.

On the target machine, the malware also deposits two DLLs: sqlite and jnidispatch (deleted once the process is completed) in the user’s AppData local directory. It will also create an sqlite file in the same directory. The file name is always in the form AppDatalocalTempd+\d{30,}. tmp. The stolen credentials will be stored in this database before being sent to C2.

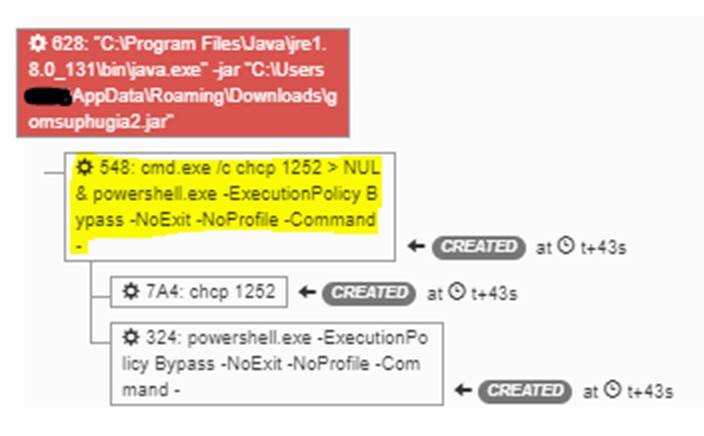

The malware will also run cmd.exe to launch Powershell. As the command is very specific, it is a good way to detect the execution of malware on a machine.

Conclusion

Our CyberSOC has been following this attacker for several months. If the main lines of his modus operandi have not really changed, it has however evolved to be more discreet. To our knowledge, he is the only one to use this malware.

We have also noticed an intensification and diversification of its activity. While it targeted more particularly English companies or English subsidiaries of international groups, since the beginning of the year its campaigns have been aimed at various companies located in Europe and the United States.

For each of its campaigns, the attacker commits significant means: a large number of compromised email addresses for the dissemination of malspam, several compromised web servers to host its payloads, several C2 etc.. This suggests that he has the means and a certain technical level.

Finally, the malware code is also interesting. While a lot of stealers are interested in crypto-currency wallets (in addition to the classical credentials), this one focuses on quite specific software such as Tortoise or Squirrel.

If for the moment this malware is only used for credentials theft, it is not impossible that the attacker may develop it or use it for other purposes. Indeed, its modularity makes it easily customizable.

IoC