30 June 2025

Author:

André Henschel

Cyber Security Analyst

In early July, the CyberSOC investigated a phishing incident which led to a compromised account. Fortunately, additional security measures prevented the adversary from gaining further access, minimizing the impact. However, this incident led us to delve deeper into the phishing tactics employed. In collaboration with the World Watch team, our investigation uncovered a widespread phishing campaign likely targeting thousands of users across several countries, with a focus on Europe. Remarkably, this campaign has been active for over a year, highlighting the persistent and evolving nature of the threat.

Our investigation was initiated following an incident that occurred in early July, where we detected unusual sign-in attempts from one user account. The analysis revealed that the user was victim of a phishing attack. The phishing email contained an HTML attachment and was sent from a spoofed domain resembling a legitimate company in the same industry as the target company. The HTML attachment was mainly made up of a few <meta> tags and a <script> tag which pointed to a npm package hosted on the jsDelivr content delivery network (CDN).

<script src="hxxps://cdn[.]jsdelivr[.]net/npm/libramat283@4[.]1[.]12/library/compass[.]min[.]js">

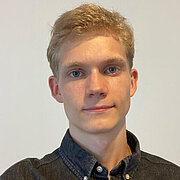

</script>The Node Package Manager (npm) is a widely used package manager for the JavaScript programming language. Requesting the JavaScript file returned highly obfuscated code as displayed in Figure 1.

Similar obfuscation techniques have been reported by Sekoia in their Tycoon2FA analysis and were likely done using the open-source javascript-obfuscator.

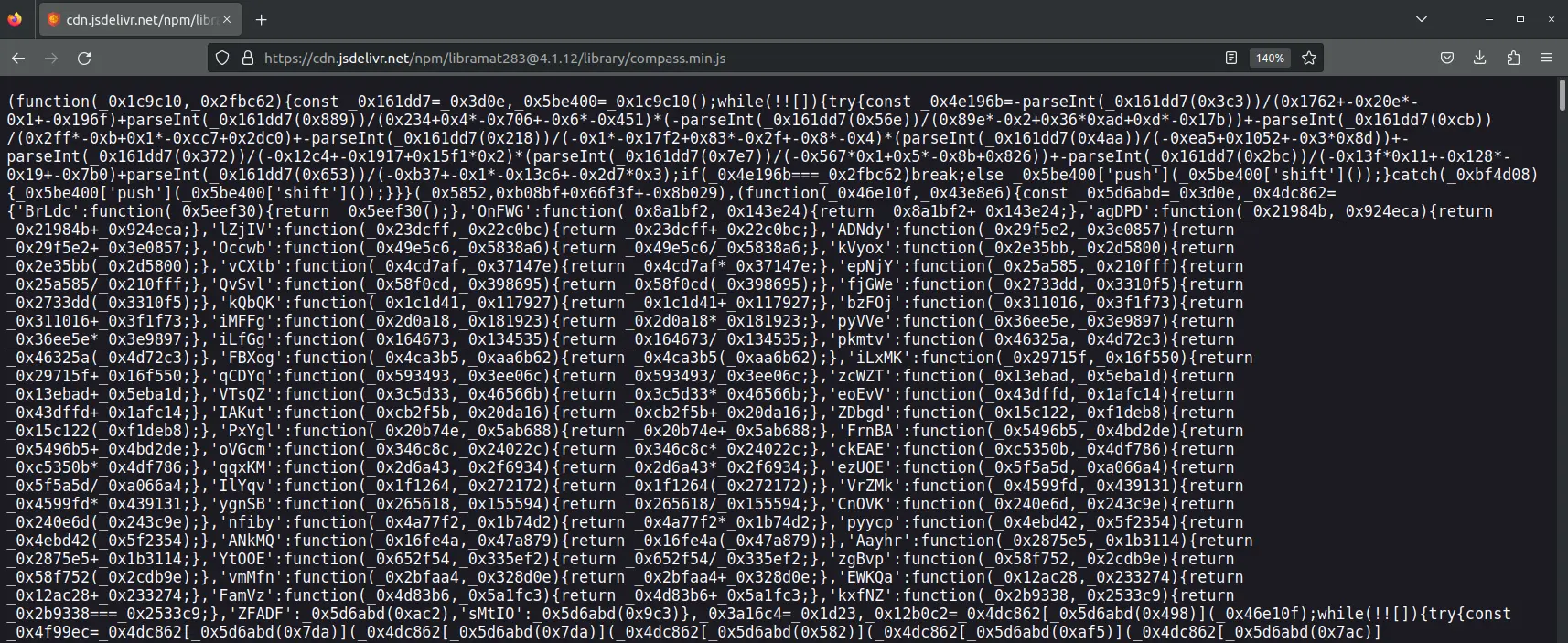

The deobfuscated code revealed a config which contained the values for the destination to which the user should be directed. The target URL was made up of a base URL, which in this incident was hxxps://fastflow[.]online/wlc/, as well as an additional identifier. The following request to this URL then returned a fake OneDrive page which acted as redirector. Clicking one of the links on that page resulted in an M365 phishing page being retrieved from the domain calmiquello1778[.]com.

Further investigation on the domain fastflow[.]online showed that it was hosted on the IP 47.253.40[.]255. This IP had many more domains associated with it in the recent past. Checking it on VirusTotal also showed hundreds of communicating files, all of which were HTML files. This led to our suspicion of this being part of a larger phishing campaign, which should prove to be correct.

Identifying the Adversary’s Infrastructure

With the IP “47.253.40[.]255” as a starting point, we continued our investigation and identified more IPs which had high numbers of similar communicating HTML files and associated domains. Checking the “Date resolved” values indicated a timeline of when the IPs were used by the adversary.

IPs associated with redirector domains

IP | Resolved Date - first domain | Resolved Date - last domain |

13.52.156[.]46 | 2024-07-03 | 2024-10-30 |

13.57.116[.]250 | 2024-11-03 | 2025-01-31 |

3.22.133[.]223 | 2025-02-03 | 2025-03-04 |

47.253.40[.]255 | 2025-03-03 | Current |

Many of the domains associated with the IPs had exclusively HTML files communicating with them. These HTML files contained similar properties as the phishing attachment we observed in the previously described incident. Therefore, it is highly likely that these domains were also used as redirector domains hosting fake OneDrive pages.

Based on the resolve dates of the domains, the adversary’s infrastructure can be traced back to early July 2024, indicating that this campaign has been ongoing for more than a year.

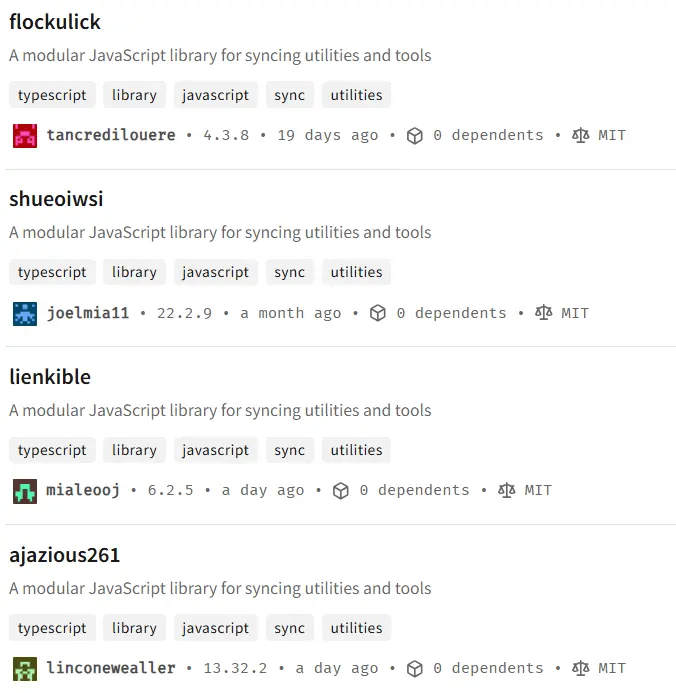

Having identified the malicious IPs associated with the redirector domains we proceeded to take a closer look at the HTML files communicating with the adversary’s infrastructure. While in our initial incident the HTML phishing attachment contained a link to the npm package “libramat283” on jsDelivr, we noticed that other HTML phishing attachments contained URLs to other npm packages and other hosting platforms. Based on the HTML attachments sent to our customers and those available on VirusTotal we identified the following hosting methods used to load the malicious JavaScript files:

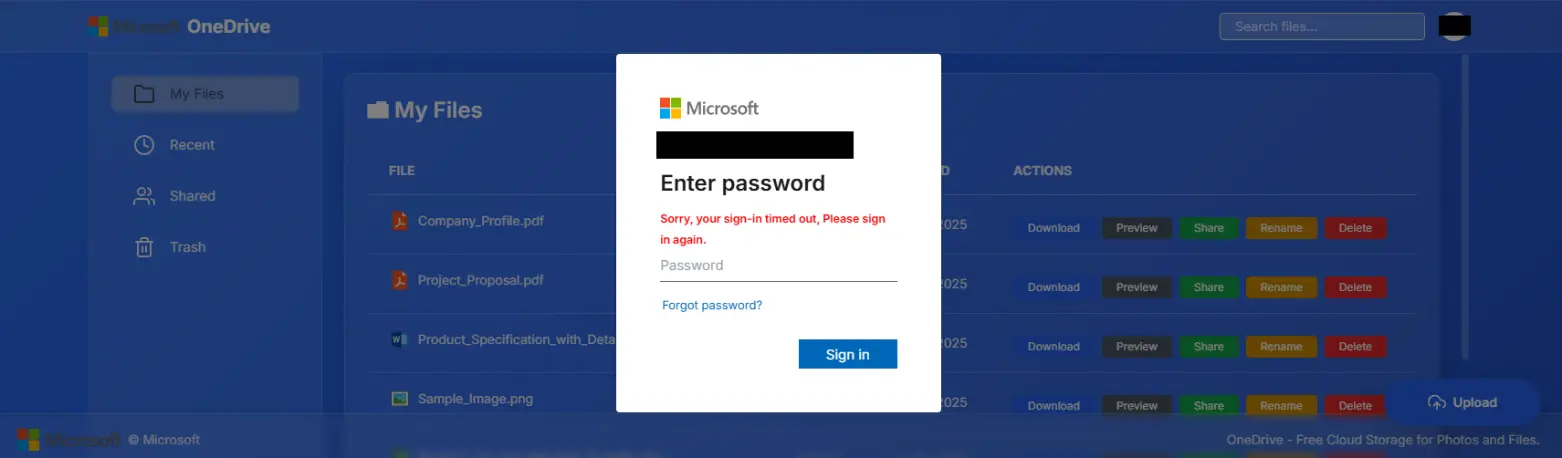

The following Timeline shows when and for how long the different hosting methods were used, based on the first submission dates of the HTML phishing attachments in VirusTotal.

As the timeline shows, the adversary has mostly focused on using files in npm packages hosted on jsDelivr to deliver their malicious JavaScript code to the victims. We have found ~60 npm packages associated with this campaign.

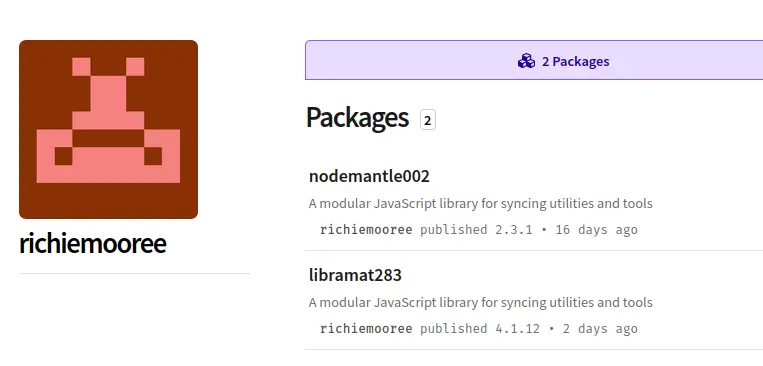

Many of the npm packages were already marked as malicious when we discovered the campaign. In some cases however, the associated files were still accessible on jsDelivr. The same issue was mentioned by Checkpoint in 2023 where an adversary also used npm packages on jsDelivr as part of a phishing campaign. In the campaign we observed, the adversary furthermore ensured the continued accessibility of malicious JavaScript files by frequently creating new npm packages every few days or weeks. For example, the creator of the npm package “libramat283” had two packages with obfuscated JavaScript files which were created two weeks apart.

Further investigation led us to more active packages which we reported to npm and jsDelivr.

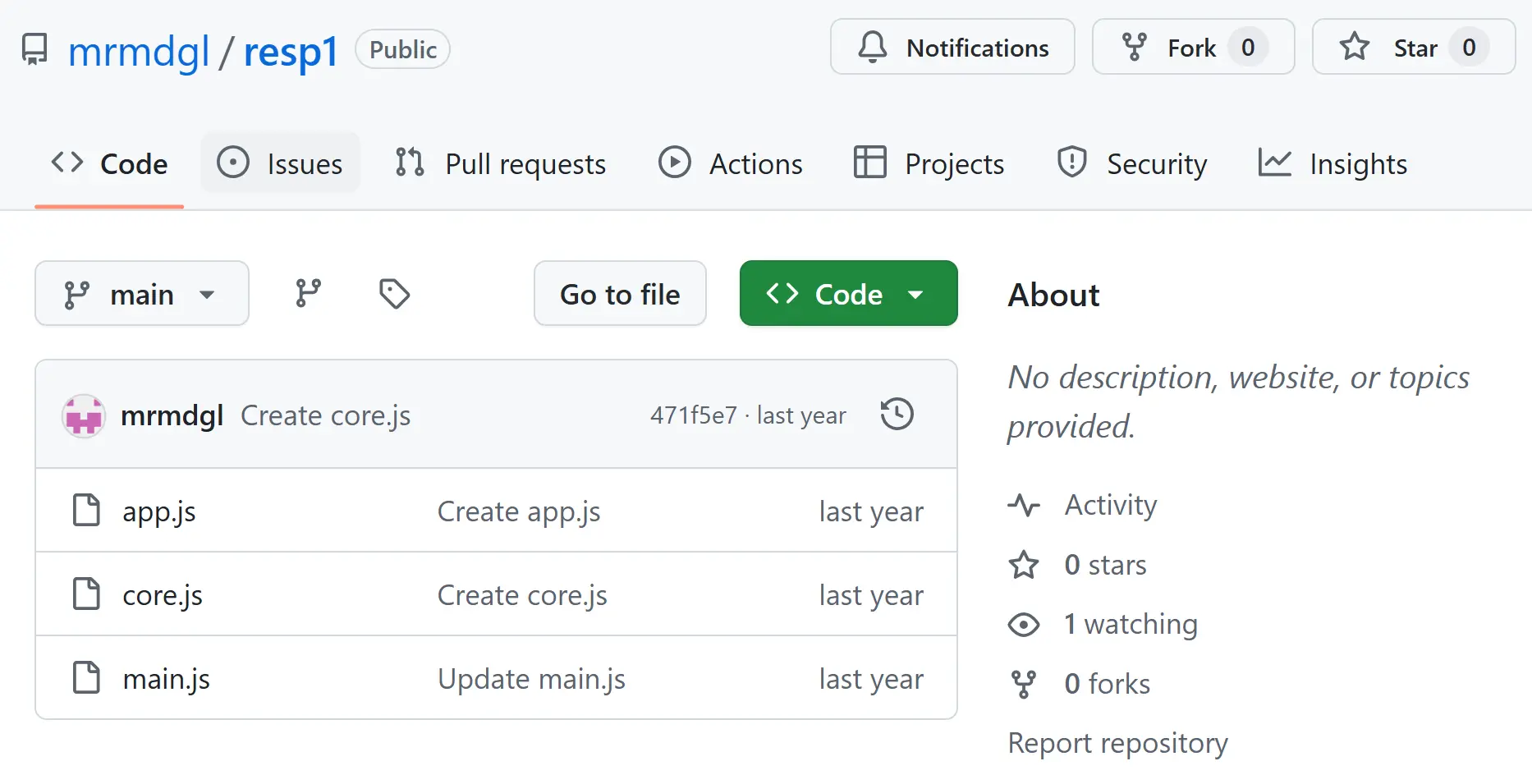

As illustrated in the timeline, the adversary utilized GitHub repositories before transitioning to npm packages. These were all created by the user “mrmdgl” which itself was created on July 8, 2024. Investigating this account revealed more insights into the evolution of this phishing campaign. It started with the first repository, named “resp1”, to which the three files “main.js”, “core.js” and “app.js” were added.

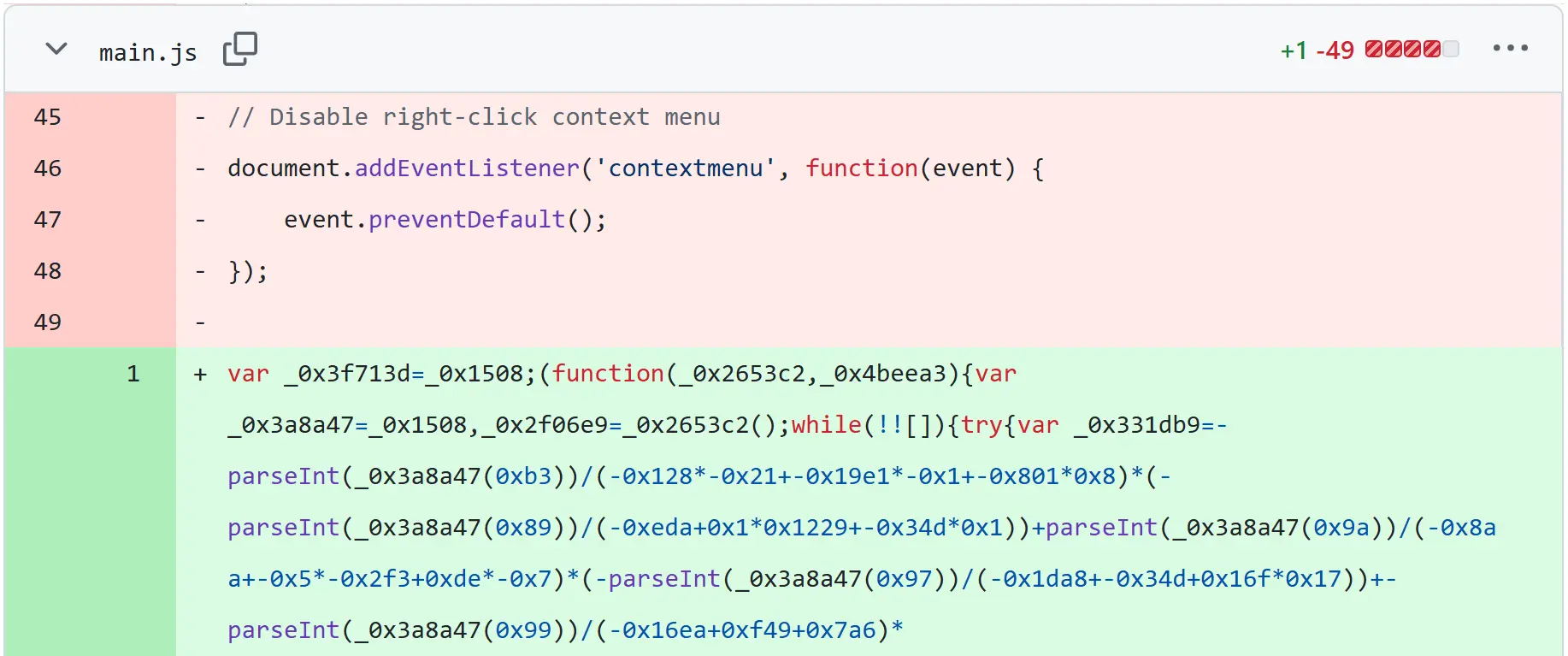

The initial version of “main.js” was an unobfuscated version of a malicious JavaScript. The second commit then updated this file to an obfuscated version with similar obfuscation as in the more recent files of the campaign.

Versions of the files “core.js” and “app.js” seen in the GitHub repository were hosted on staticsave.

hxxps://static[.]staticsave[.]com/cdnjsme/core.js

hxxps://static[.]staticsave[.]com/cdnjsme/app.js

Beginning September 2024, more repositories with similarly obfuscated JavaScript files followed. These were then hosted on statically.io and differed slightly from the initial JavaScript files in the “resp1” repository.

Another notable activity of “mrmdgl” was the addition of the Evilginx2 phishing framework repository. To this repository there was one commit which added the domain “grabberhub.assetswix[.]icu” as an endpoint to capture session details.

The phishing emails we observed being sent to our customers came from email addresses with spoofed domains. The majority of the companies associated with the legitimate domains were part of the manufacturing or engineering industry.

Legitimate domain | Spoofed sender domain |

dmsplast.com | dmsplasts[.]com |

yushinautomation.com | yushinautomations[.]com |

strojimport.com | strojimports[.]com |

bmoautomation.nl | bmoautomations[.]com |

starcellspa.com | stercellspa[.]com |

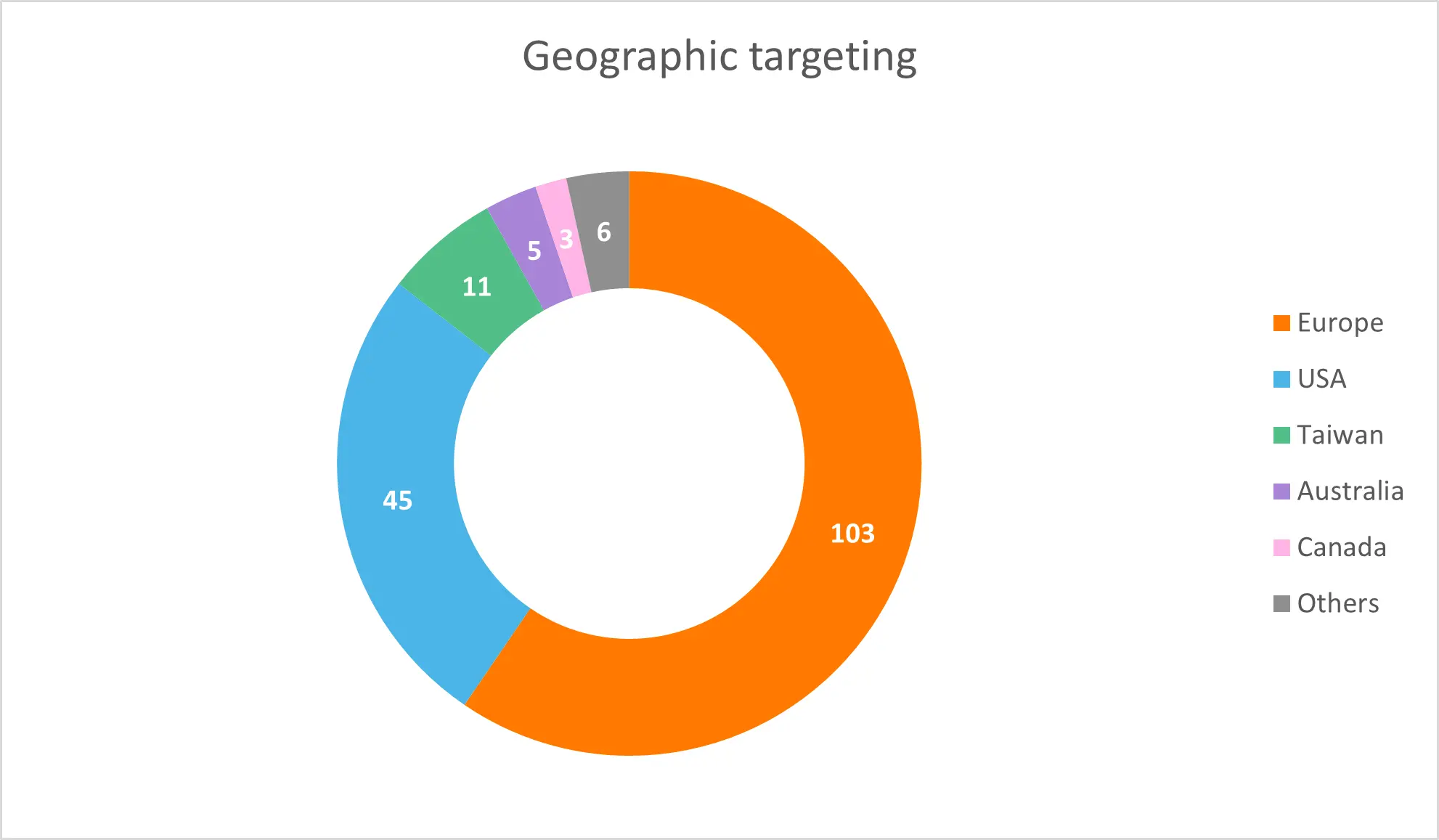

Many of the HTML phishing attachment file names which were uploaded to VirusTotal contained domain names associated with legitimate companies. Assuming that these were the companies to which the phishing emails were sent, we calculated a geographic distribution of the targets. With 173 companies as base, this is a rough estimation of what regions the phishing campaign may have focused on. Figure 10 shows this distribution where 60% were targets in Europe, followed by the USA with 26%. Within Europe the most targeted country was Germany with 36 companies.

In this first of two parts, we detailed the discovery and investigation of a sophisticated phishing campaign that has been abusing npm packages, GitHub repositories, and public CDNs for over a year. The investigation began with an incident involving suspicious sign-in attempts against a user account, which led us to identify a malicious phishing attachment. Further analysis uncovered a broad adversary infrastructure, including IPs hosting redirector domains, numerous malicious npm packages, a GitHub account, and spoofed domains used to send phishing emails. The timeline of this infrastructure reveals that the campaign has been active for more than a year.

In the second part, we will dive into the detailed attack flow, highlighting the use of the adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) framework Evilginx and anti-debugging techniques embedded in malicious JavaScript files. Furthermore, we will explore detection and mitigation approaches to help defend against this kind of threat.