11 May 2021

Authors: Adam Ridley, Diana Selck-Paulsson

This piece is the second part in a series on how cyber extortion (Cy-X) and ransomware threat actors make use of neutralization techniques to justify their malicious behavior. The first part introduced our research approach, and gave a more detailed overview of how neutralization theory can be applied to better understand the person or people participating in a crime.

If someone were to commit a crime, they might excuse their actions by saying “no-one got hurt”. This process is called the ‘denial of injury’. It’s a form of technique called neutralization, which is a way for people who participate in a crime to drift away from accepted norms for a time without compromising societal morality (Sykes and Matza, 1957).

An understanding of the use of neutralization by those engaging in cybercrime, whether deliberately or subconsciously, is important because it presents another potential lever through which the tidal wave of cyber extortion crimes may be countered.

Using language like “no-one got hurt” could indicate that the person believes the action did not count as a ‘crime’, or that they are trying to distance themselves from being labelled as a ‘criminal’.

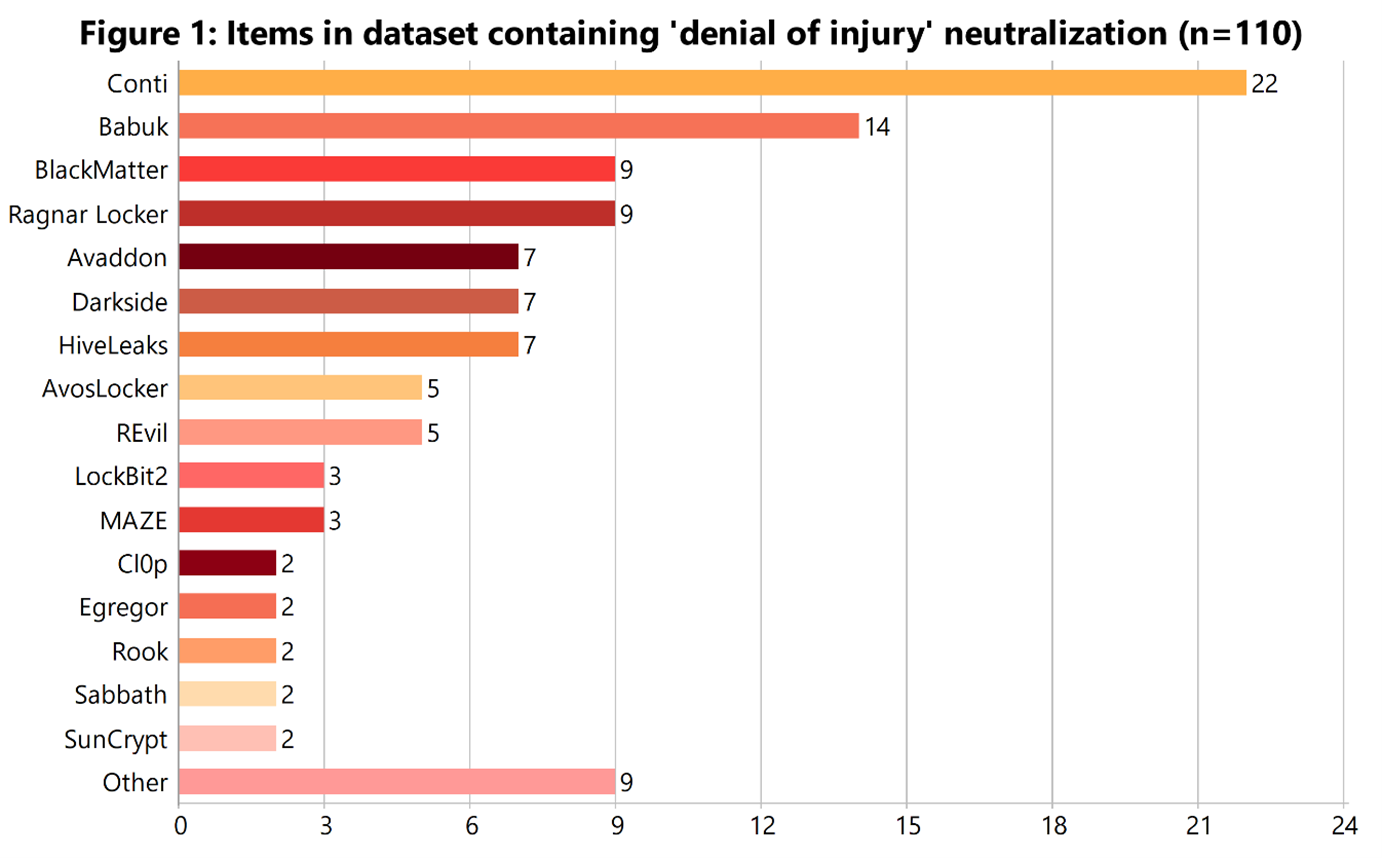

In our study of ransomware and cyber extortion threat actors, this form of neutralization was the most prevalent. In what follows, we will present examples of how people engaging in this activity have sought to reframe their behavior as being non-deviant. We will demonstrate some of the techniques, practices and discursive strategies that threat actors employ to position their malicious behavior as a ‘service’.

In some cases the crime is presented as being of direct benefit to the victim by exposing security weaknesses and vulnerabilities, akin to a ‘bug bounty’ program. In other cases, it is projected as broadly making digital society safer from organizations that recklessly store sensitive data insecurely.

In other instances, we found that threat actors co-opt or imitate the type of language and terminology that one might ordinarily find in a business setting. We believe that this too is a form of ‘denial of injury’, as this process appears to be attempting to position the behavior as legitimate business activity between a service-provider and a client.

We have also found that threat actors have rationalized or ‘neutralized’ their behavior by explicitly or implicitly suggesting that their victims can easily afford to pay for the ‘service’ (of being extorted). An approach like this was also described by Sykes and Matza in 1957 when they considered how people engaging in vandalism might seek to neutralize their delinquent behavior.

There are several points about our methodology to raise before proceeding further. In this piece, and in the remainder of the series, we will explore the evidence of neutralization techniques present in our dataset of 232 unique content items. These include ransom negotiation chats, press releases, announcements and leak sites sourced from 35 different threat actor groups.

We made use of the ‘Framework Approach’ as a guide for the thematic analysis of our qualitative dataset (Ritchie and Spencer, 1994). This involved familiarizing ourselves with the data, developing and applying a tagging or ‘coding’ system, charting the coded segments, then mapping and interpreting the data using neutralization theory (Sykes and Matza, 1957).

There are also alternative social science theories that could be used to interpret and understand the phenomenon of cyber extortion in different ways. For instance, dramaturgical analysis (Goffman, 1959) might be used to explore how members of threat actor groups select language to portray themselves as fulfilling a ‘role’ of being professional businesspeople, in a similar manner to an actor performing a role on a stage.

We do not propose to encompass the rich diversity of explanatory theories within a single piece or even within this series as a whole. Our point is simply that neutralization theory should not be viewed as the sole authoritative approach.

Furthermore, as members of the cybersecurity industry, we as researchers are not positioned as objective observers of a social phenomenon. Our subjectivity and bias can be seen in the use of terms such as ‘threat actor’ and ‘cyber extortion’ that are intrinsically value-laden.

The implications of this subjectivity are important and are worthy of further inquiry, but we will not do this here. (For one such deeper exploration of this issue, see Law and Singleton, 2000.)

We also acknowledge that the dataset is not representative of all negotiation chats. Nor should the writers be seen as fully representing all individuals within a threat actor group. What we have studied is only what we have been able to access and scrape from the dark web.

We were also not the intended audience of the dataset but are instead interpreting material in a secondhand manner. This contrasts with direct interviews of consenting participants, either with members of threat actor groups or victims themselves. Interviews such as these would provide rich and different insights into this area, and remains an avenue for future research to pursue.

Finally, there are language limitations to consider, as many of the threat actor groups were not writing in their first language. This makes it more difficult to precisely gauge their original intentions in the texts. Please note that in the discussion that follows, quotes have not been edited for grammar or syntax.

Perhaps the most egregious examples of denial of injury were where the threat actors framed their malicious behavior as being a service, either to the victim or to society more broadly. We found that this approach was used most notably by Ragnar_Locker, Sabbath, Babuk, Maze, Pysa and Quantum.

By way of example, in the quote from a leak page below, Ragnar_Locker argued here that their actions were not harming the victim. Instead, the threat actor used language to position themselves as trying to help the victim’s partners and clients because the victim was being negligent and irresponsible (by not paying the ransom).

If the executives of [REDACTED COMPANY NAME] is really cares about their confidentiality and security of partners and clients, they should contact us to negotiate conditions of the deal with us. . . . If they will not contact us [by the deadline], then everyone will knows about such an negligence and irresponsibility from their side.

Ragnar_Locker, Leak Page 1

This tactic seems to be intended to distract the reader from the malice of the attack and the injury that the attack was causing to the victim.

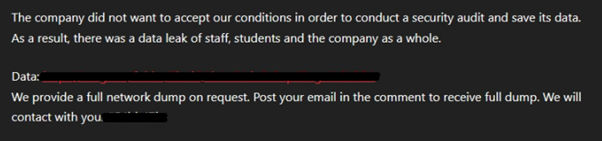

In contrast, Sabbath and Ragnar_Locker can both be seen in the examples below justifying their actions by claiming that their goal was to demonstrate weaknesses in organizations’ security (i.e. “a security audit” or “bug hunting”). In doing so, these threat actors implied that their cyberattacks were not causing injury to the victims.

Instead, they appeared to extend an offer of help to protect victims from (other) malicious actors who might misuse stolen or leaked data, even if these ‘other actors’ were a constructed bogeyman.

Companies under attack of Ragnar_Locker can count it as a bug hunting reward, we are just illustrating what can happens. But don't forget there are a lot of peoples in internet who don't want money - someone might want only to crash and destroy. So better pay to us and we will help you to avoid such issues in future.

Ragnar_Locker, About Us 1

Sabbath’s neutralization in particular is quite thin. They later leaked the victim’s data because the victim did not pay, which is an inherent contradiction. Sabbath on the one hand claimed to be helping instead of harming, yet their extortion and blackmail tactics indicated the complete opposite.

It appears that Sabbath was trying to shift accountability for the leak by portraying it as a last resort that would not have occurred had the company accepted and paid for the “security audit”. The writer therefore appears to be capable of making moral decisions by organizing their actions according to a moral priority.

It is also plausible that this is a persuasive technique to convince the victim, or other future victims, to pay the ransom by reframing the extortion as a service rather than a crime.

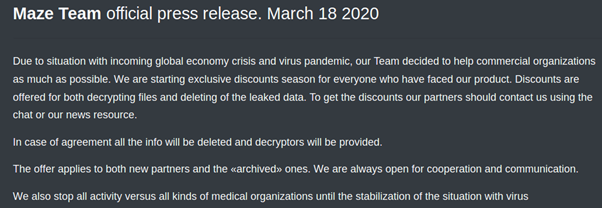

In addition to framing attacks as a direct ‘service’ to the victim, Maze also positioned themselves alongside Julian Assange or Edward Snowden by claiming that their attacks help to make digital spaces safer.

Some people like Julian Assange or Edward Snowden were trying to show the reality. Now it’s our turn. We will change the situation by making irresponsible companies to pay for every data leak. You will read about our successful attacks in news more and more.

Maze, Press Release March 2020

In this way, Maze argued their cyberattacks were not primarily about inflicting injury to victims but were instead justifiable because they forced irresponsible companies to change their behavior and improve their cybersecurity practices.

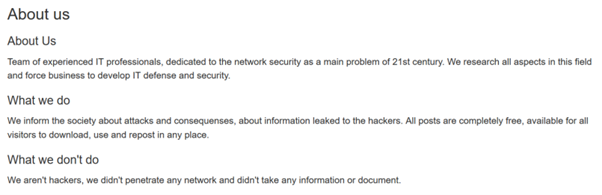

Quantum used a similar approach on their ‘About Us’ page. As can be seen below, they argued that their cyberattacks were benevolent and that their overall goal was to force businesses to develop stronger security measures.

The text is framed in such a way that considerations of the existence of injuries to victims are excluded by the appeal to the broader goal of motivating organizations to improve their cybersecurity.

Since Quantum excluded the impact and injury caused to victims by these actions, Quantum was, by omission, denying that an injury occurred or that a victim even existed. The latter is a different type of neutralization technique that will be explored further in the next research piece in this series. On both counts though, Quantum was trying to persuade the reader that their actions can be considered a service that benefits society.

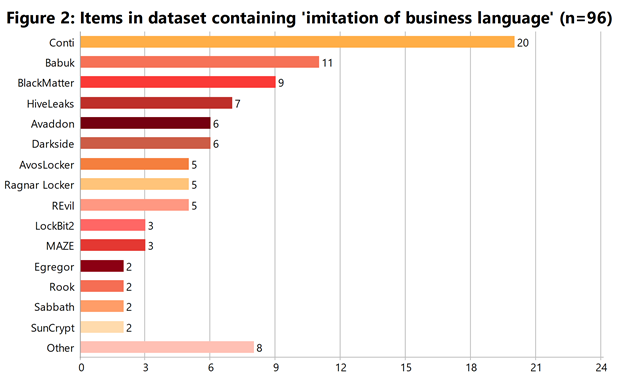

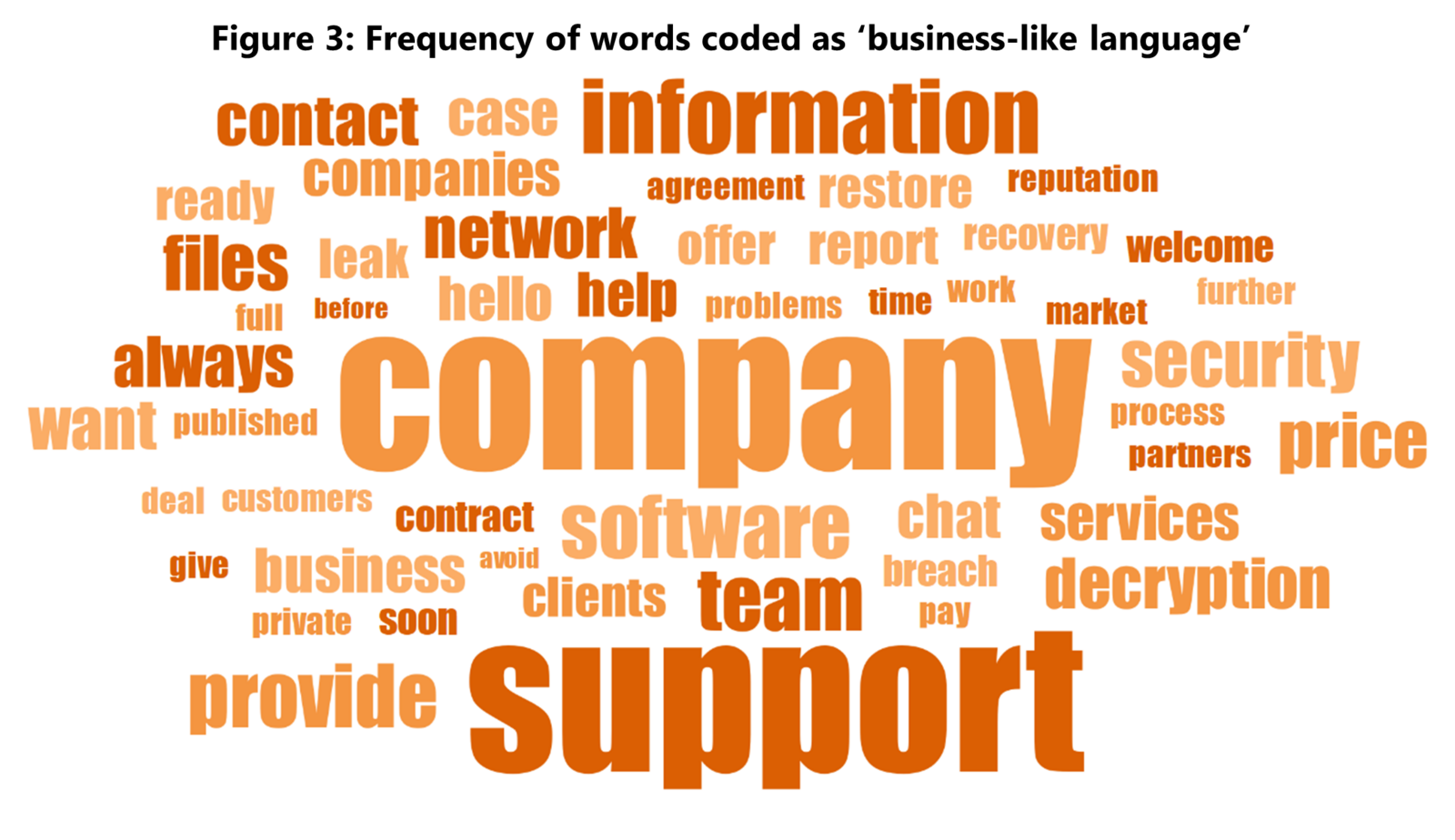

We have also observed threat actors frequently co-opting language that would normally be found in a business environment, with 154 instances of this across 96 unique items in our dataset. We propose that by employing discourse that imitates businesses, threat actors were trying to paint their cyberattacks as legitimate business activity. Figure 2 below depicts the number of unique items in the dataset containing business-like language, and Figure 3 is a word cloud highlighting key words from the individual coded segments.

We posit that this pattern is an extension of the ‘denial of injury’ neutralization technique. This is because the attempt to legitimize the attack logically also leads to the conclusion that the ransom payment is in fact a payment for legitimate services between two businesses.

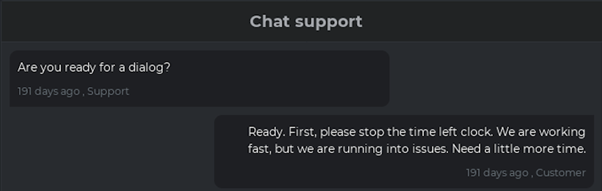

The example of this technique that occurred most frequently was where the threat actor used discourse such as ‘customer support’ or ‘client’, with 63 unique items in the dataset that included this type of language. This had the effect of reframing the interaction with victims as a business transaction rather than as an extortion of a victim.

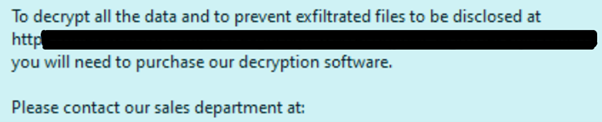

The second group of terms included phrases such as ‘sales departments’, ‘products’ and ‘our software’, implying that threat actors were commercial business entities. These terms appeared in 21 items in the dataset, with some examples included below:

In addition to these, we also observed threat actors such as REvil, Maze, Conti and Rook using language evocative of a ‘sales pitch’. For example:

We've developed the best data encryption and decryption system available today. Our competitors allow themselves to lose and destroy their victims' data during the encryption or decryption process, making it impossible to recover the data. We don't allow ourselves to do that. So you should be glad you were infected by our guys, not our competitors. This means that when you pay for the decryption, you can be sure that all your data will be decrypted.

REvil, Customer Portal 1

REvil appears to be trying to position itself as a superior player on the ‘market’ through the use of a sales pitch like this. Terms such as ‘best system’ and ‘our competitors’ are similar to what legitimate service providers might use when trying to convince prospective customers.

In one ransom note, Maze presented a similar statement that reads like a sales pitch designed to reassure customers prior to a purchase. However, from our perspective as members of the cybersecurity industry, the ‘sales pitch’ obscures the fact that the interaction between threat actor and victim is an extortion, not a purchase of a legitimate service:

What about guarantees? We understand your stress and worry. So you have a FREE opportunity to test a service by instantly decrypting for free three files on your computer! If you have any problems our friendly support team is always here to assist you in a live chat!

Maze, Ransom Note 1

Finally, a further 46 items in the dataset used what we are describing as ‘miscellaneous business terms’. These terms do not necessarily have a common thread that groups them together, but are still certainly reminiscent of a business-like environment. Examples included ‘brand reputation’, ‘foundation of our business’, ‘market’, ‘promise of non-disclosure’ and ‘collecting and analyzing information’.

Interviewer: What makes REvil so special? The code? Affiliates? Media attention?

REvil: I think it’s all of that working together. For example, this interview. It seems like, why would we even need it? On the other hand, better we give it than our competitors. Unusual ideas, new methods, and brand reputation all give good results.

REvil, Interview 2

To put it simply - the chances that Hell will freeze are higher then us misleading our customers. We are the most elite group in this market, and our reputation is the absolute foundation of our business and we will never breach our contract obligations.

Conti, Negotiation Chat 11

Maze Team is working hard on collecting and analyzing the information about our clients and their work. We also analyzing the post attack state of our clients. How fast they were able to recover after the successful negotiations or without cooperation at all.

Maze, Press Release June 2020

In sum, we have observed significant numbers of instances where threat actors co-opt or imitate language that might be used by legitimate businesses in the course of legitimate transactions. This could be indicative of the use of neutralization, through which threat actors deny that encryption and extortion activities are causing injury to the victim.

We propose therefore that the use of this language has a reframing effect for the threat actor, positioning their behavior as a commercial service offering.

Sociology does offer other theoretical frameworks that might interpret this evidence differently. For example, dramaturgical analysis (see Goffman, 1959) suggests that the threat actors might use business language for performative purposes due to a desire to be perceived as professionals, fulfilling the role of the ‘digital elite’ instead of being petty thieves or criminals.

Applying dramaturgy to this dataset would open up the possibility of new interpretations and explanations, though this falls well beyond the scope of this series.

A third form of denial of injury that emerged from the data was where the threat actor believed that the victim could afford to pay for the damage inflicted. This goes beyond the simple definition of denial of injury where the threat actor claims that nobody was hurt by the action, or that the action was actually beneficial. As Sykes and Matza wrote in 1957 using the example of vandalism:

For the delinquent, however, wrongfulness may turn on the question of whether or not anyone has clearly been hurt by his deviance, and this matter is open to a variety of interpretations . . . it may be claimed, the persons whose property has been destroyed can well afford it.

Sykes and Matza, 1957: 667

In support of this theory, we also observed 12 threat actor groups on 46 occasions explain that their underlying motivation was to make money.

Our business does not harm individuals and is aimed only at companies, and the company always has the ability to pay funds and restore all its data.

BlackMatter, Interview 1

The bigger the company’s capitalization is – the better. There are no [other] main factors. . . Our targets are businesses, capitalists.

LockBit, Interview 2

Some threat actors, such as Babuk, went further to state that they chose to target profitable businesses or organizations with sizeable cashflow precisely because the underlying motivation was to make money.

We do not attack victims in some countries such as Russia, Poland or other post-Soviet countries. For the simple reason - they simply don't have the money to pay for our services.

Babuk, Interview 2

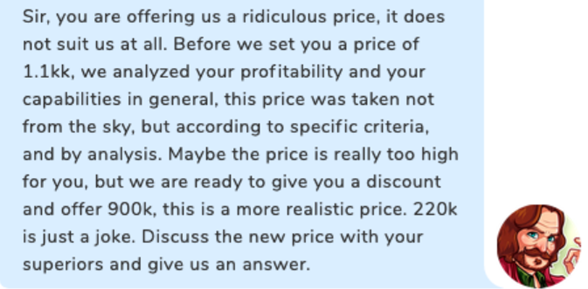

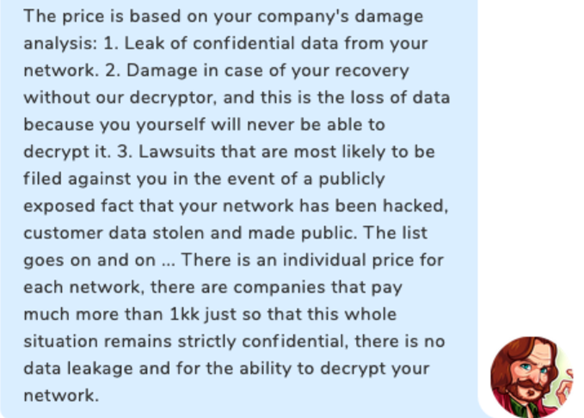

A common technique that we observed in negotiation chats was threat actors telling their victims that the ransom prices were set according to what they believed the victims could afford to pay.

For example, Avaddon was quite explicit in one negotiation:

Later in the same negotiation, Avaddon gave further clarification about the ‘damage impact analysis’ that they used to determine the ransom price, as well why they believed the victim could afford to pay:

BlackMatter took a similar approach by explaining that the ransom amount was set on the basis of the victim’s financial statements. They argued that the victim was ‘crying poor’ in their claim to not be able to afford to pay, since the victim’s financial statements appeared to show the opposite.

Your company has over $ 200 million in revenue. I think you can pay this price. But we see business here, and these are negotiations. . . . Well, if you are such a poor company, please provide us with your tax reports and we will give you a discount based on them. We want to understand in which group you are of those who are ready to negotiate and pay? or will you be a laughing stock on our site of leaks and suffer reputational losses, as well as not recover your files?

BlackMatter, Negotiation Chat 2

These justifications were often based on victim’s estimated annual revenue, rather than annual profit. One of many such examples can be seen from Conti’s negotiations:

According to the public records your revenue is 47,000,000$, so this price is reasonable. . . . We don't think, that our estimates are incorrect. Your financial reports are somewhat more reliable, than your word here and now. . . . We looked throw your finance records, bank accounts and know that you have more available funds. We are ready to give you some discount, but that price is not reasonable. We own a lot of private data which cost much more.

Conti, Negotiation Chat 8

There is spurious logic in threat actors’ usage of revenue as a basis for the ransom price calculation, as revenue is clearly different to profit. A high-revenue organization may be experiencing a significant budgetary deficit, which in turn would hamper the victim’s capacity to afford to pay the asking price.

Yet it is worthwhile returning to Sykes and Matza who noted that the denial of injury, and its associated ‘wrongfulness’, was open to a variety of interpretations on the part of the delinquent (1957: 667). These interpretations do not necessarily need to be accurate. They simply need to be sufficient in the mind of the offender to serve as a neutralization.

From the examples above we can clearly see that some people who engage in cyber extortion have exhibited behaviors similar to the neutralization technique of ‘denial of injury’. There is evidence to suggest that some members of threat actor groups are reframing their activity as being a legitimate service or commercial product available for purchase.

However, this neutralization twists reality. A power imbalance exists between the threat actor and the victim, with the extortion process having clear consequences should the victim choose not to pay (i.e. the leak of sensitive data). Furthermore, the victim has not willingly entered into this so-called ‘business transaction’.

Still, this insight into the mindset of threat actors raises important questions worthy of further investigation. Why is it that some people engaging in cyber extortion behavior are attempting to deny the injury experienced by the victim? Is framing the extortion as a ‘service’ simply a way to convince victims to pay the ransom, potentially at a higher price? Or are threat actors’ neutralizations a genuine attempt to temporarily reframe their personal morality to enable them to engage in crime?

Furthermore, if we accept that a major motivation for cyber extortion is financial, can victims reduce ransom prices in the negotiation phase by somehow utilizing the tendency of some threat actors to neutralize their behavior? Perhaps there are ways for negotiators to reflect back the inconsistency in the new temporary morality that people engaging in cyber extortion behavior are constructing for themselves.

In the next piece, we will consider the neutralization technique known as the ‘denial of victim/victimhood’. As will become clear, there is often overlap between this and the ‘denial of injury’, though we do observe subtle differences in the way the two techniques are employed.